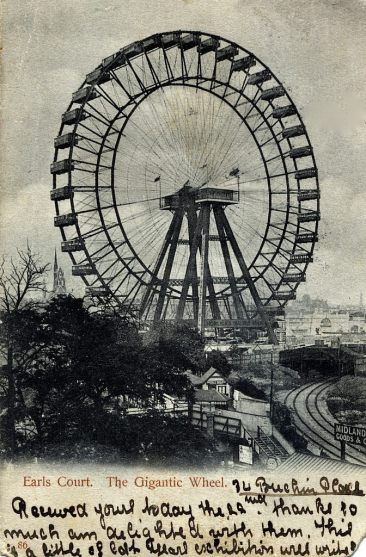

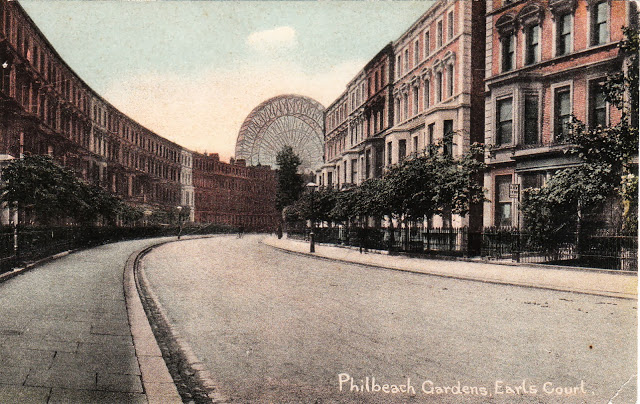

This British postcard was mailed to Mr. W. Roberts, 3302 Lindell Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri on 22 January, 1904. The unknown sender posted it from what is today an upscale area of South Kensington, London. The message reads, “34 Brechin Place. Received yours today the 22nd. Thanks so much, am delighted with them. This is a little of Earls Court exhibition. Will write.”

The wheel at Earls Court, London, was built by Maudslay, Sons, and Field, for the Empire of India Exhibition, and opened to the public 17 July, 1895. The project’s engineer was H. Cecil Booth, who recalled, “One morning in 1894, W. B. Bassett, a retired naval officer, one of the managing directors of the firm, entered the drawing office and called out ‘Is there anyone here who can design a great wheel?’ There was dead silence, whereupon I put up my hand and replied, ‘Yes, I can, sir.’ Basset’s answer was ‘Very well, get on with it at once. It is a very urgent matter!’” (Ferris Wheels: An Illustrated History by Norman D. Anderson.)

The design and build process resulted in a 440-ton wheel that reached a height of 220 feet. It had 40 cars, each of which carried up to 40 passengers. On a clear day, from the apex, riders could see out across London and as far as Windsor Castle. At night, the wheel was a sight in itself, with a spotlight affixed to it and the entire structure and passenger cars decorated with incandescent lamps.

“Those who make the ‘circular tour’ will be able to enjoy most of the advantages of being up in a balloon without any of the risks attendant upon aerial navigation,” assured the 2 February, 1894, Westminster Budget, before the public opening. Anderson reveals in his book Ferris Wheels that the first passengers were probably George, Duke of York (later King George V), and his wife, the Duchess (later Queen Mary). Bassett was one of the Duke’s old shipmates and arranged the clandestine ride.

The Earls Court Wheel was based on the magnificent Ferris Wheel built for the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exhibition by the eponymous George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr. (1859-1896). There had been smaller “pleasure wheels” in the past, but the Ferris Wheel overshadowed them at approximately 26 stories tall. Although the wheel was a singular success, carrying an estimated 38,000 passengers daily who each paid 50 cents per 20-minute ride, Ferris was cheated of his percentage of the take and was in litigation up until the time of his death, which occurred not long after the Earls Court Wheel opened.

The 23 November, 1896, issue of the New York Times reported, “George W. G. Ferris, the inventor and builder of the Ferris wheel, died to-day at Mercy Hospital, where he had been treated for typhoid fever for a week. The disease is said to have been brought on through worry over numerous business matters. He leaves a wife in this city, and friends in mechanical and building circles all over the country.”

The Earls Court Wheel was equally moneymaking. A 19 December, 1896, Guardian newspaper article discussed its use and profitability, “From the opening of the wheel in May till [sic] it closed in October, [it] carried nearly 400,000 people, and earned from rides on the wheel alone £20,237. The bank holidays were one of the principal sources of revenue. At the August Bank Holiday last year they took over £621. This was largely composed of first-class traffic at 2s. each.”

During its years of operation, the wheel experienced only one incident of note: On the evening of 28 May, 1896, the drive mechanism broke, stranding those in the cars. “Everything possible was done to calm the trapped passengers. Seamen climbed the wheel’s framework, carrying food and drinks. When the wheel still was not repaired by midnight, Grenadier guards gathered around the wheels base and played music to entertain those who were spending the night in a way not expected. Although mechanics worked throughout the night, the wheel did not start turning again until 7 o’clock the next morning. As the weary passengers disembarked, each received a five-pound note as a benevolent gesture on the part of the management,” wrote Anderson in Ferris Wheels.

A more humorous view of the event was published in the 2 June, 1896, issue of The Journal: “At first the people in the wheel went into a panic. The crowd below knew that they were stuck, yet they could not resist confirming this impression by throwing out of the windows frantic notes and statements of their helplessness. The rapid American communicated with the crowd by putting a note in his silver cigarette case and tossing it down to become a highly prized souvenir in the pocket of a street arab. The cook used bad language, the married woman out for an innocent lark wept copiously, the mother of five bestowed her children as only a mother of five can do, and went tranquilly asleep, while her husband paced the aisle of the car and kept informing an old and aged maiden lady that he would give a sovereign for a cigarette. The servants of the Great Wheel Company scaled the outer skeleton of the frame and put ropes in the hands of those who were suffering for food, telling them they could draw up whatever they wanted. As far as I can make out from the newspaper reports, starving people in London, having an opportunity to gratify their appetites, are given to demanding beer and whiskey; for it was beer and whiskey that went up in the greatest quantities.”

Always envisioned as a temporary attraction, the Earls Court Wheel closed in October 1906 and was slowly demolished during the following year. In its lifetime, it carried an estimated 2.5 million riders. Ω

Well I currently live 10 miles from 3302 Lindell Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri where the postcard was mailed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Utterly amazing!

LikeLike

I was never allowed on Ferris Wheels as a kid because Dad had been stuck on them several times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The only ride I was ever stuck on was The Pirates of the Caribbean at Walt Disney World. We came to a stop in the big open bay where the pirates are firing on the Spanish town. The staff had to wade out and pull the boats to the side so we could exit through a secret door into a lane in the back of the property. Loved every minute of it.

LikeLike

I’ve never been stuck on ride, although Dad used to joke I set a wooden roller coaster on fire. It was the first time I’d ever been on one, and I loved it and they let me and him and stay on for several turns. Finally he said we had to go, but later that night, the coaster caught fire and he would joke it because I wore it out. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person