On 5 October, 1722, in Ziefen, Canton of Basil-Land, Switzerland, a healthy male infant was born and christened Peter Recher. Either before his birth or slightly thereafter, his Anabaptist father, Martin Recher IV (1692-1760), was exiled from the canton. This was probably at the declaration of the Anabaptist Bureau, which was, in 1699, created to capture and banish members of the then-heretical group now known as Mennonites. Anabaptists believed that a public confession of sin and faith followed by an adult baptism was required and that infant baptisms were meaningless because babies were incapable of choosing baptism freely. Little Peter may not have seen his father until 1730, when Martin was allowed to return from exile in Oberdiessbach, Canton Bern, after his unorthodox beliefs were either pardoned or abandoned.

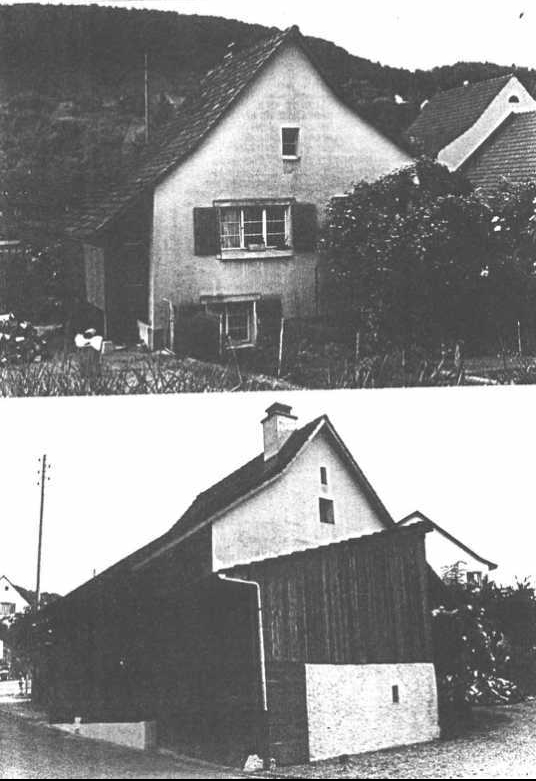

Martin Recher, and probably also his wife, Elizabeth Rudy (1690-1748), were lacemakers. The desire for lace, ribbons, trim, and bows was strong, but lacemakers often struggled to profit from the detailed, time-consuming craft. The Rechers had a number of children, so providing for them was probably always challenging. However, the family did have a solid home, built in 1610 by an earlier generation. It was more than 110 years old when Peter was born, and now, almost 300 years later, it is still lived in by modern-day Rechers.

We know nothing of Recher’s life until his decision to immigrate to the Colony of Pennsylvania in 1751, when he was an unmarried 27-year-old. Remarkably, two letters sent by Recher to his family in Ziefen were translated and published by Klaus Hein in the October 1992 issue of Mennonite Family History. The first letter, written in 1751 provides a full and harrowing description of the effort it took to reach the ship Queen of Denmark on the English Isle of Wight then make the ocean crossing to Philadelphia.

“To Marti Recher in Ziefen, in the area of the Basel-Land in Switzerland. My friendly greeting and the following report to you, much-beloved father, brother, sisters, brother-in-law and siblings,” the letter begins. “Now I will tell you a little of the journey. Down the Rhine [River], everything went fairly well, up to the town of Arnheim in Holland. Here the helmsman drank so much beer and brandy that he could hardly see straight. He steered the ship straight into the landing pier. People standing nearby were sure that the ship would break apart, but through God’s guidance, nothing happened to our ship.

“On the 23rd of June, we arrived in Rotterdam, where we stayed for six weeks. From Rotterdam, across the Tollen Hund [English Channel], we went to a town in England called Cowes. We stayed there for ten days. Then we started our voyage over the big ocean.

“For the first eight days on the ocean, we had unfavorable winds, so that we reached an island called Santa Maria [southernmost island of the Portuguese Azores]. There we waited for six days, and once the wind became favorable we continued our voyage and had good winds for the most part.

“On the 20th of September, we were caught in a storm. The wind broke our middle big mast. Waves battered against our ship so that it sounded like the thundering of several cannons. The ship rolled on to its sides to such a degree that one thought one might drown at any moment. This wind lasted from 4 o’clock in the afternoon until 4 o’clock in the morning. The waves washed high over the ship.

“Several times we had excellent winds so that we traveled 10 to 12 miles in an hour. Our journey across the ocean, from Cowes to Philadelphia, took nine weeks….” In completely favorable winds, the trip took seven weeks.

Gottlieb Mittelberger, a German who crossed the Atlantic the year before Recher, wrote, “When the ships have for the last time weighed their anchors near [Cowes], the real misery begins with the long voyage. On the voyage, there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of sea-sickness, fever, dysentery, headache, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably.

“Add to this want of provisions, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, anxiety, want, afflictions and lamentations, together with other troubles…. The misery reaches the climax when a gale rages for two or three nights and days, so that every one believes that the ship will go to the bottom with all human beings on board. In such a visitation the people cry and pray most piteously…. These poor people often long for consolation, and I entertained and comforted them with singing, praying and exhorting; and whenever it was possible and the winds and waves permitted it, I kept daily prayer-meetings with them on deck. Besides, I baptized five children in distress, because we had no ordained minister on board. I also held divine service every Sunday by reading sermons to the people; and when the dead were sunk in the water, I commended them and our souls to the mercy of God.”

Recher did not reveal the conditions on the ship in which he traveled, but told his family, “I was well and healthy the whole time. But during the time on the ocean, I must have regretted being there as many times as there are minutes in a year. My dear friends, I advise no one to come, for the journey is dangerous and troublesome.”

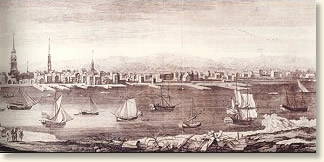

Worse for wear, the broken-masted Queen of Denmark slunk into the port of Philadelphia on 4 October, 1751. “Three-hundred-fifty passengers were on our ship, of which 29 died,” he wrote. “Eighteen of them were children below the age of four.”

Once in Philadelphia, Recher quickly met up with or heard news of other kindred and friends who had made the trans-Atlantic voyage before him. “Now I will tell you about [Uncle] Hans Recher’s son. Hans Hemmig’s wife [talked with] him in the city of Philadelphia. His name is Johannes. Cousin Heiny Buser also visited me, which made me very happy. The city in which he lives is called Yorktown [York, Pennsylvania]. I also heard that Marti Tschopp is in this country. Further, I heard that Jogy Rudy [is here].

“I am presently living with Hans Hemmig and have taken service with a shoemaker for one month. He promised to pay me £10. When I finish working for him I plan to work on my own. All the work is done in the customers’ homes.” (Hans Hemmig (1742-1820) was farmer and former resident of Ziefen, who now rests in the Hemmig Family Cemetery, Cumru Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania.)

Gottlieb Mittelberger noted in his description of Penn’s Colony, “No trade or profession in Pennsylvania is bound by guilds; every one may carry on whatever business he will or can, and if anyone could or would carry on ten trades, no one would have a right to prevent him; and if, for instance, a lad as an apprentice, or through his own unaided exertions, learns his art or trade in six months, he can pass for a master, and may marry whenever he chooses.”

The second letter, a reply to one received from his family in Ziefen, was written from York on 28 October, 1753. He began with another warning against sailing to the Colonies, despite the opportunity found there.

“I am glad that the lace-making trade is satisfactory again. Otherwise, people in Canton Basel-Land would be bad off since many depend on lace-making work. I wish that all mouse-poor people could be in this country and would not have any debts. [Here] they [can] earn their daily bread properly if only they have the desire to work. But I advise all who can make it through over there not to move to this country. Much money is used up in getting here, and once here it is all used up. Then the misery starts and one hardly knows how to help oneself. For all those who have bread, it is as good to eat over there as it is here in the new county.”

Next, Recher filled in his family on his own location. “Before Easter 1752, I moved from Hans Hemmig closer to the city of York where cousin Heiny Buser lives. I work here in the trade under a master craftsman and have each week £3 and 2 or 3 batzen [Swiss coinage struck in Bern from the 1500s to the 1900s] as wages. Everything is three or four times as expensive as in Switzerland. A pair of men’s shoes cost £3, a pair of women’s shoes 1 taler [a silver coin used throughout Europe for centuries]….

He answered a family question concerning the kinsman mentioned in his 1751 letter thus: “I know nothing further of Johannes Recher. Though I have asked much about him I have not been able to learn anything. I have a mind to put him in the weekly paper.” Other cousins, he knew of, however. “Fritz and Hans Recher have moved further through Virginia… They are even more sloppy house-keepers than they were in Switzerland.”

Recher then composed a long description of Pennsylvania, probably to sate his family’s expressed curiosity. “This country is similar to Switzerland in many respects…. There are as many varieties of trees here as in Switzerland, perhaps even more. Here in Pennsylvania, there are mainly oak trees, but also many nut trees some chestnut trees, poplar, walnut trees, mulberry trees, and sassafras trees.

“You, in Switzerland, find sassafras in your pharmacies and it is very expensive. Here it is plentiful and it has a pleasant odor. Farmers make tea from its blossoms. There are many other trees that I cannot name. Blueberry bushes abound. I have not yet seen juniper and fir trees, but in Virginia, there are supposed to be many fir trees. There are also pine trees, but of a different kind than those in Switzerland. Cedar trees grow in two variations, namely white and red. Wild boxwood trees also grow here, but they are not as pretty as the domesticated variety. There are many more sorts of trees, but it is unnecessary to describe them all.

“Many varieties of herbs grow here, some of them precious, as well as precious roots. The herbs all are of a different stature from those in Switzerland, and the wulkraut [probably kidney vetch or mullein] looks the same.

“The farmers grow all kinds of grains, but for the most part, wheat and rye. We have buckwheat or heathergrain. Weltschkorn is not planted. Many potatoes, beets, turnips, beans, and all sorts of garden vegetables are grown, just as in Switzerland.

“There are also big rivers and creeks, and many good springs. Fish in the creeks may be caught by anyone.

“Vines and grapes grow here, but they are not used to make wine, rather they are eaten only from the stem. Wild vines and grapes are as plentiful as you could wish. The wine which is consumed here all comes from Offania [Spain?] across the ocean. A half measure of wine costs nine cents at the inn, but it is as strong as brandy. The drinks, which are most common here, are cider, beer, and whiskey, which is distilled from wheat.

“They have valuable horses here, which can be ridden four to five miles in an hour. Cattle is the same in Switzerland, as are the sheep and pigs, But there are no goats.

“Many wild animals can be found: deer, bear, wolf, fox, rabbit, and turtles weighing up to 15 or 20 pounds. There are also many snakes: green, grey, and black ones, and rattlesnakes. The birds are as in Switzerland, except that we do not have storks or vultures. Eagles are plentiful…. In the summer there are so many fireflies, which fly at night, that one thinks fire flames were flying in the air.

“Here the days are two hours shorter in the summer and two hours longer in the winter. The summer is warmer, but the winter just as cold as in Switzerland. Snow is the same. The English leave their cattle outside, in the woods, all winter long, as they have no stables. Many of their animals freeze to death. The Germans have stables, and the English are starting to follow their example.”

Of the spirituality of his fellow colonists, he told his family, “Many faiths and religions may be found here: The Catholics have no rights and are not allowed to stand against others. Further, there are Herrnhutters, Mennonites, Separatists, Quakers, Newborns, New Mooners, Saturday Baptists, which hold their Sabbath on Saturday, many Sunday Baptists, Dunkers, and Jews.

“There are many who form their own little groups. Some in this country have even preached as though no eternity is to be expected, and have said that a nice little bag of money is enough to be the right helper in need, and believe as if there is no God in heaven. They may no longer preach like this, for it is forbidden with a high penalty.”

Mittelberger echoes Recher in his own writings, “There are many hundreds of adult persons who have not been and do not even wish to be baptized. There are many who think nothing of the sacraments and the Holy Bible, nor even of God and his word. Many do not even believe that there are a true God and a devil, a heaven and a hell, salvation and damnation, a resurrection of the dead, a judgment and an eternal life; they believe that all one can see is natural. For in Pennsylvania every one may not only believe what he will, but he may even say it freely and openly.”

Recher eventually settled near Latimore, Adams County, Pennsylvania, where many Swiss and German immigrants had already built prosperous farms. In his first letter, Recher hinted at this as the cause of his eventual migration to Maryland. “There is also much good land, but it has all already been claimed in Pennsylvania, and it is as expensive as in Switzerland.”

Before 1758, while in Adams County, Recher met and married Mary Anna Leatherman (b. 1739), daughter of Gottfried Leatherman, Sr., and Hannah Holtz. Mittelberger wrote of local weddings he’d witnessed, sounding scandalized, “If a man in Pennsylvania is betrothed to a woman and does not care to be married by an ordained preacher, he may be married by any Justice, wherever he will, without having the banns published, on payment of 6 florins [a British coin worth two shillings]. It is a very common custom among the newly married, when the priest has blessed them, to kiss each other in presence of the whole church assemblage, or wherever the marriage ceremony takes place.”

Baptismal notations exist in the records of Lower Bermudian Lutheran and Reformed Church in Latimore for two of Peter and Anna’s daughters. The first, Susanna, was christened 27 December, 1757, and Elizabeth Margaret, on 27 December, 1758. A third daughter, Mary Ann, was born about 1760.

By 1762, Recher had purchased 45 acres in Frederick County, Maryland, and later added another 50. Recher’s land was in the vicinity of what became Wolfsville and may have been selected due to the nearness of his wife’s kin. On 15 August, 1763, a son named after his father was born on the new farm. A final child and second son, John, arrived circa 1765.

Recher became a naturalized citizen in Frederick, Maryland, 12 September, 1771.

The area’s first Lutheran church was built during the 1770s with the assistance of congregant Peter Recher. It was located at the area’s earliest settlement, known as Jerusalem, about six miles from the Recher farm. The church at Jerusalem appears to have played a large role in Peter’s later life and also that of his children. In 1781, when his daughter Mary Ann wed her uncle, Revolutionary War Lieutenant Godfrey Leatherman, Jr. (1748-abt. 1839), it was later remembered that the couple walked the six miles together to marry in the church her father helped construct.

In 1785, Recher’s daughter Elizabeth also married a Leatherman—Joseph (1766-1837). Son Peter, Jr., married Elizabeth Protzmann (1769-1836). They had eleven children and relocated to Montgomery County, Ohio.

Recher’s 1753 letter spoke of his desire to see his family in Ziefen. “I am still planning, the Lord granting me health and life, to journey to Switzerland once my little bag of money has gained some strength…. Meanwhile, everything committed into the hands of the good Lord.” However, it is unlikely he ever made another harrowing voyage across the unfriendly Atlantic.

Recher died in Wolfsville on 19 March, 1791, sadly without a Will revealing details of his lands and possessions. He became—it is thought—the second person buried in Jerusalem Cemetery. His grave marker yet stands, crudely carved into rough fieldstone. In the same letter, he chastised, “Father, when you write to me again, do not send so many greetings, since I cannot deliver them all.” Born far away from that hillside, he lies in the soil of an adopted home, as do so many of his hopeful immigrant kin. Ω

I’m surprised an Anabaptist has the children baptized.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if his mother was not of the same mind and insisted on baptism–or what the penalty was for not baptizing your children. It may have been too great to take the chance.

LikeLike

“In the summer there are so many fireflies, which fly at night, that one thinks fire flames were flying in the air.” That’s a beautiful description.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ann are you related to the Recher Family and if so have you taken a DNA test through the many providers. I think I might be related to Johannes Recher, who arrived in Philadelphia in 1838 as an indentured servant. Thanks

LikeLike