Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962), regarded as the “mother” of forensic science, was also the first female U.S. police captain, although the title was honorary. In 1936, Glessner Lee came by a sizable inheritance—her father was cofounder of the International Harvester Company—and she used it to help build a Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard Medical School. It was during the decade afterward that Glessner Lee crafted many of the 20 known Nutshell murder dioramas.

Corine May Botz wrote in The Nutshell Murders of Unexplained Deaths that “[Lee] took a special interest in training police officers because, as the first to arrive on the scene of a crime, they had to recognize and preserve evidence critical to solving the case. At the time, most police officers inadvertently botched cases by touching, moving, or failing to identify evidence. Lee was also extremely interested in better integrating the work of, and communication among medical experts, police officers, forensic investigators and prosecutors.”

In the Nutshell Study above, farmer Eben Wallace was found hanged in his barn. His wife told police, “When things did not suit Eben he would go out into the barn, stand on a bucket, put a noose around his neck, and threaten suicide. I always talked him out of it. On this afternoon, he made the usual threats, but this time I did not follow him to the barn right away. When I did, I found him hanging there with his feet through a wooden crate.”

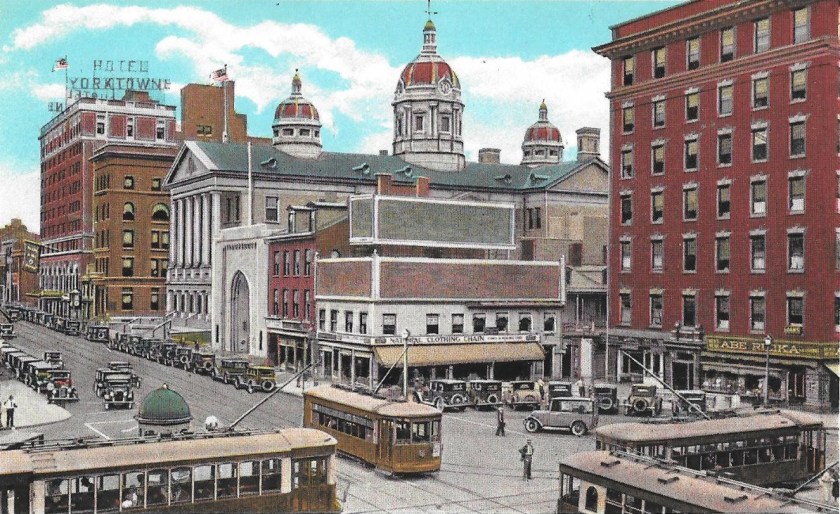

Continental Square in York, Pa. Courtesy of the York History Center.

Continental Square in York, Pa. Courtesy of the York History Center.