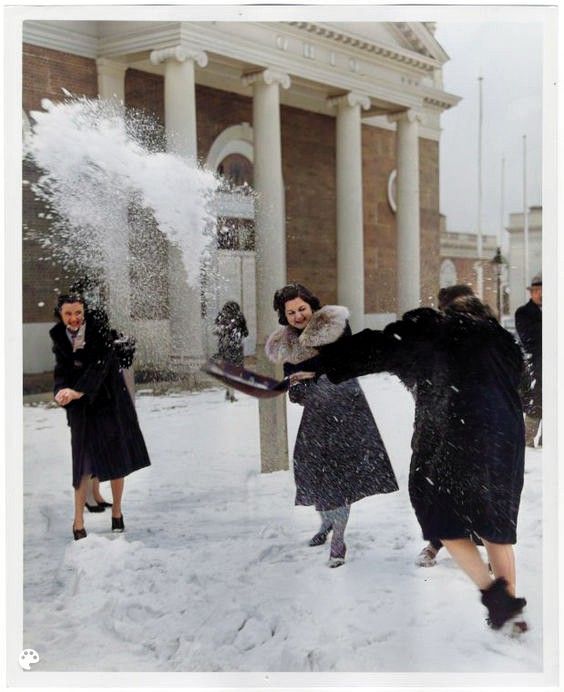

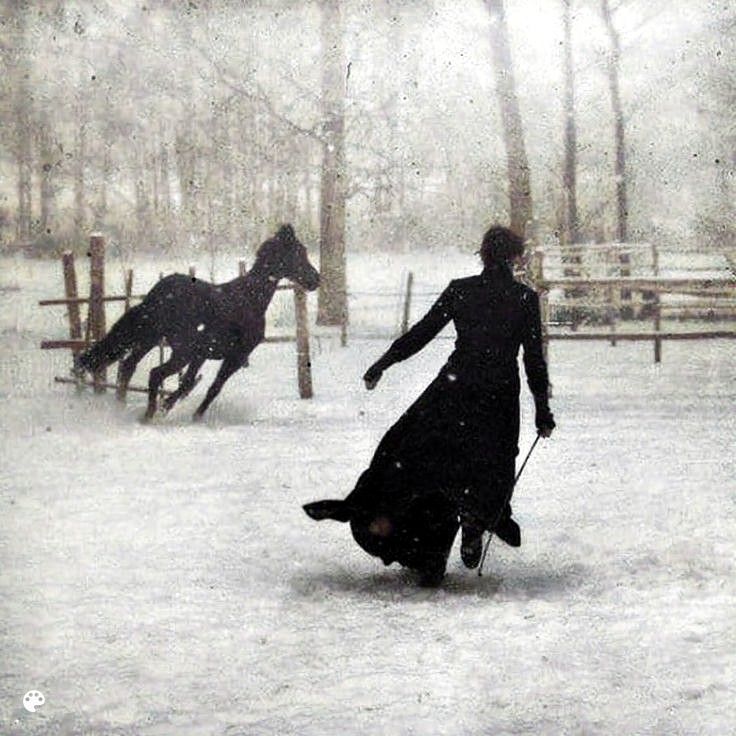

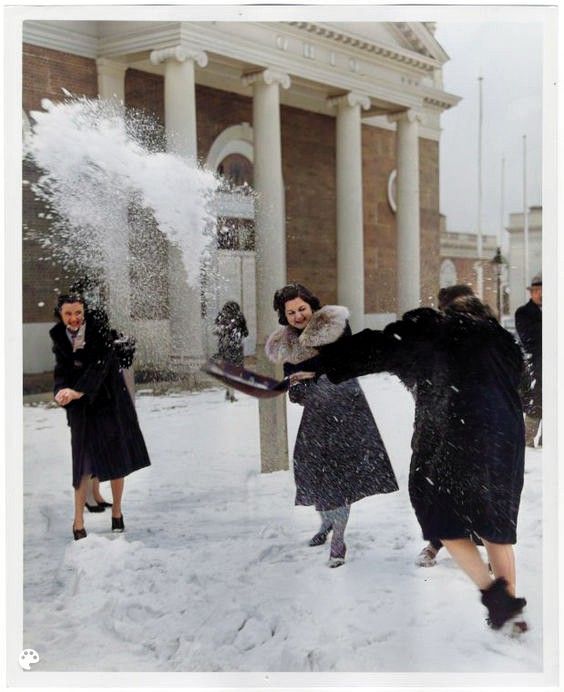

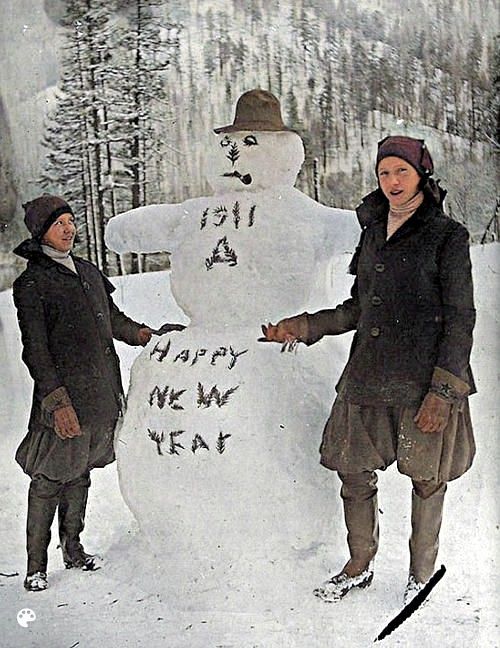

It seems like a good time to remember once again the winters of Yore…*

*All black and white images were colorized.

Ω

It seems like a good time to remember once again the winters of Yore…*

*All black and white images were colorized.

Ω

“She sleeps in peace, dear sister sleeps—

Art thou forever gone?

No, we will see thee soon again,

Where parting is unknown”— In Memory of Mary Frey by Her Sister CMB

This angelic child, pictured at the start of what should have been a long life, was Edyth Embery, born 5 March, 1909, in Frankford, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. She was the daughter of Dr. Francis Patrick Embery (1867-1939), a Philadelphia otorhinolaryngologist, and his wife Miriam Fairbairn Wilson (1875-1948), whom he wed in early 1899. (The 12 February Philadelphia Inquirer described Miriam as wearing “heavy corded white silk, trimmed with chiffon and lace and carried bride roses. The flower girl, maid of honor, and bridesmaids wore white organdie and carried white carnations.”)

Francis Embery, known as Frank, was born at Foxchase, Philadelphia County, to William Henry Embery (1840-1914). Frank’s father was, by 1872, head of the Assay Laboratory of the United States Mint. Previously, he’d served as a sergeant in Co. A, 1st New Jersey Cavalry, during the Civil War. Frank’s mother was Annie Elizabeth Manning (1841-1921), who was of Irish descent.

“Young John sat fascinated all day, watching the trajectories of shells above the trees of the mountain, followed by the little puffs of smoke that marked their targets.”

Just short of his 97th birthday, in May 1950, John Caleb Leatherman spoke to reporter Betty Sullivan from the Hagerstown Daily Mail about his life and boyhood memories of the Union blue and Confederate grey armies’ descent on Frederick County, Maryland. The interview he gave is a boon for historians, as firsthand accounts from the Jackson and Catoctin districts—including Myersville, Wolfsville, Ellerton, Harmony, Jerusalem, Pleasant Walk, Highland, and Church Hill—are almost nonexistent. I recounted two of these pertaining to George Blessing, “Hero of Highland,” in a previous article, and Leatherman’s secondhand testimony was also integral to that reportage, as the Leathermans and Blessings knew each other well.

John Leatherman was born 15 December, 1852, in Harmony (also known for a time as Beallsville)—a nascent town that never fully took root. Today, it is a series of farms and old buildings set along Harmony Road. John was the son of farmer George Leatherman (1827-1907) and his wife, Rebecca Elizabeth Johnson (1827-1908), who married 16 December, 1847. The 1860 Census records that George Leatherman’s farm was worth more than $8,500 and his personal estate more than $4,000—some $360,000 in today’s dollars. At that time, the family had six children, the oldest of whom, Mary (b. 1848) was enumerated as deaf and mute.

Although he was listed in several Union draft registers of the Jackson District, it’s likely that Leatherman, who was in his 30s during the war, would have opposed serving. He was a devoted member of the Brethren, a pacifist German Baptist sect also known as the Dunkards, was elected to the clergy of the Grossnickle Meeting House in 1865, and would become a church elder in 1880. In an earlier article about Robert Ridgley, the longhaired still-breaker of Myersville, I wrote that Ridgley wanted to be buried near Leatherman, of whom he said, “I feel that I owe practically all from a spiritual standpoint to this Grand Good Man.”

Continue reading “Best Christmases Ever: Twenty Color Photos from Holidays Gone By”

Shadows of a thousand years rise again unseen,

Voices whisper in the trees, “Tonight is Halloween!” —Dexter Kozen

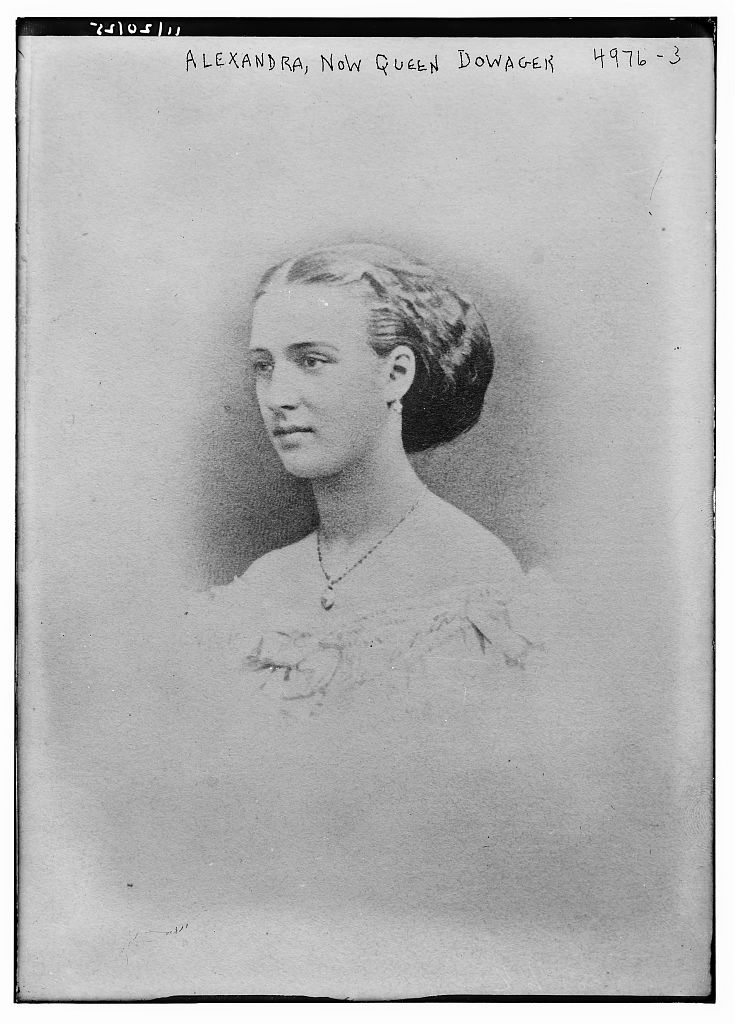

Continue reading “Preternaturally Lovely: Britain’s Queen Alexandra of Denmark”

As the Northern Hemisphere explodes with green life, let’s take a look back at rebirth celebrations of yesteryear.

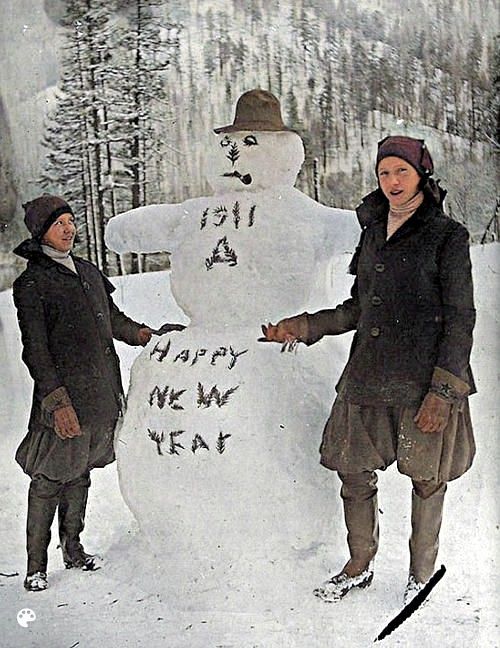

Last week, a storm brought 10 inches of snow to Western Maryland and turned my mind to snowmen of old.

In all probabilty, humans have sculpted snowmen for millenia. In 2007, Bob Eckstein, the author of The History of the Snowman: From the Ice Age to the Flea Market, told NPR that in writing his book, “I wanted to make it clear that snowman-making actually was a form of folk art. Man was making folk art like this for ages, and…maybe it’s one of man’s oldest forms of art…. [T]he further back you go, you find that people were really fascinated with snowmen.”

Eckstein says that building snowmen was “a very popular activity in the Middle Ages…after a snow came down and dumped all these free-art supplies in front of everyone’s house.” The earliest known representation of a snowman dates to that era, drawn in a 1380 A.D. Book of Hours. A century later, in 1494, Michelangelo was commissioned by Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Gran Maestro of Florence, to practice his art with snow. According to art historian Giorgio Vasari, “de’ Medici had him make in his courtyard a statue of snow, which was very beautiful.” Sadly, no one drew it for posterity.

In 1510, a Florentine apothecary, Lucas Landucci confided in his diary that he had seen “a number of the most beautiful snow-lions, as well as many nude figures…made also by good masters.” Another notable snowmen outbreak occurred just a year later, when folk in Brussels built more than 100 of them “in a public art installation known as the Miracle of 1511,” notes Atlas Obscura. “Their snowmen embodied a dissatisfaction with the political climate, not to mention the six weeks of below-freezing weather. The Belgians rendered their anxieties into tangible, life-like models: a defecating demon, a humiliated king, and womenfolk getting buggered six ways to Sunday. Besides your typical sexually graphic and politically riled caricatures, the Belgian snowmen, Eckstein discovered, were often parodies of folklore figures, such as mermaids, unicorns, and village idiots.”

“Her husband was the only one in the room, and he was asleep.”—Louisville Courier-Journal

The earthly remains of Iola M. Haley Newell are buried in Somerset City Cemetery, Somerset, Kentucky, within the casket seen above. It was almost certainly white, with a crackled paint finish and colored velvet covering the pallbearers′ handles. The rest of the gently sunlit parlor held rich photographic detail. The fireplace was surrounded by colorful Victorian art nouveau tiles. On the wall, above the harp-shaped floral tribute, a paper or cardboard image of a blooming plant proclaimed, “The Year of Flowers.” Reflected in the mirror, along with two female mourners, were more images also possibly culled from “The Year of Flowers.” Behind the black-clad ladies was the staircase to the home’s upper floor.

It is a wistfully beautiful image: A bright-colored room, burgeoning with flowers in recognition of a beloved daughter, sister, friend, and bride of little more than a year, dead before age 30. The most likely causes of Iola’s demise should have been pregnancy complications or childbirth. However, there is no record of a child born alive or dead—and if the latter, we would expect to see the stillborn infant in the casket, beside its mother.

It is also clear from the photo that Iola was not the victim of a wasting disease, rather of something that cut her down in otherwise acceptable health. Her husband, Dr. John B. Newell, survived Iola narrowly, dying a year-and-a-half later. Newell worked in a field of medicine—dentistry—whose practitioners could be easily exposed to Tuberculosis and other contagious diseases. Another possible cause for one, or both, of the couple’s deaths was typhoid. An epidemic occurred in Pulaski County in 1920, and since the disease can be waterborne, contaminated waterways may have existed in the area in the decade before, when the couple was yet alive.

Continue reading ““Everybody Loved Her”: The Mysterious Death of Iola Haley Newell”

“When old Francis died in 1913, Dad sent him off in a hearse pulled by four black horses followed by mutes carrying ostrich feather wands and a procession of friends and family in the deepest mourning possible.”—Barbara Nadel