This beautiful carte de visite (CDV) is identified on the reverse as “Elise Von Rodenstein.” When I purchased it, I had great hopes of uncovering a full biography, but this has not yet happened. The first problem I encountered was not knowing whether the snood-wearing, polka dot-dressed mother or the equally polka-dotted child was Elise. If the infant, she may have been the Elise Von Rodenstein born in 1865 or 1866 in Fort Washington, New York, United States, to German immigrant Charles Von Rodenstein and his American wife, Elise Briggs. I am skeptical of this, however, as I can find no connection to Scotland.

Elise von Rodenstein’s potential mother, Elise Briggs, was enumerated on the 1881 Census of Kingston City, Ontario, Canada, with her six Von Rodenstein children. (Interestingly, half of the children were Catholics and the other half adherents of the Church of England.) The census said that Elise Briggs was born about 1833 in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. In 1890, Elise and her children’s enumeration escaped the conflagration that destroyed most of the decade’s U.S. Census. In that year, Elise Briggs lived in Washington, D.C., with one of her other daughters. She was also likely the same woman who died in Manhattan, New York City, 28 October, 1920, aged 88.

Elise Von Rodenstein became a nun. In 1910, she was at the Sacred Heart Convent and Loretta Sisters Schools in St. Charles, Missouri, working as a teacher, By 1915, she taught at the Academy of the Sacred Heart at University Avenue and 174th Street, New York City. Between 1920 and 1930, Elise was a nun at the Convent and Academy of the Sacred Heart in Rochester, New York. She eventually became Mother Superior of a Philadelphia convent and died there of acute coronary occlusion on 9 March, 1961.

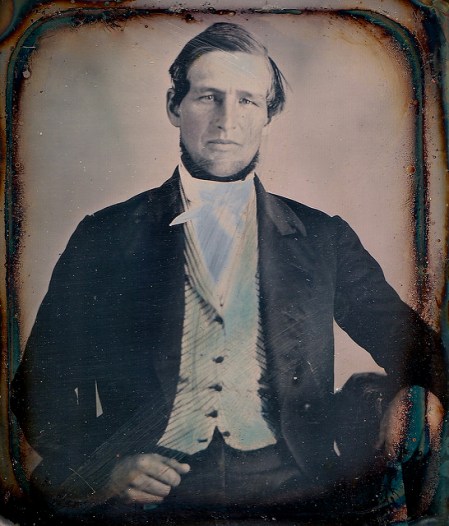

The photographer of this CDV is quite well known. Thomas Rodger (1832-1883) studied at St. Andrews University, learned to produce the silver iodide-coated paper calotypes introduced in 1841, and became an assistant at Lord Kinnaird’s studio in Rossie Priory.

During the 1850s, Rodger won multiple awards for his photographic achievements, and in 1877 he was given the International Photographic Exhibition Medal.

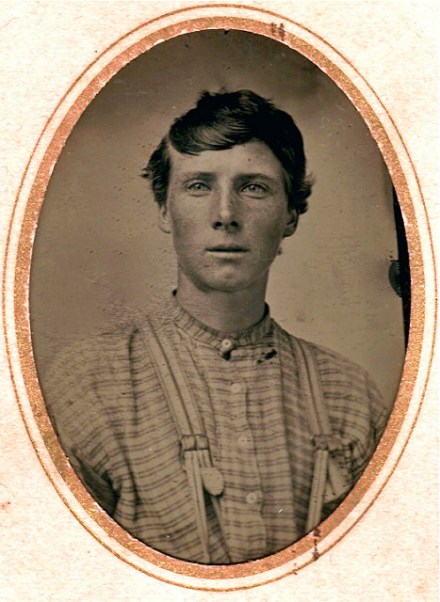

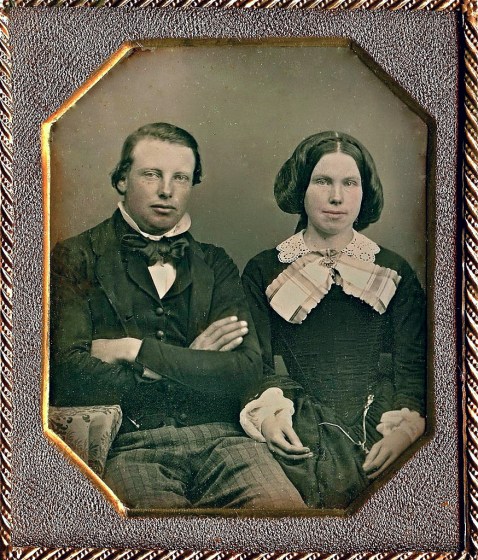

Written inside the case of this delightful daguerreotype is “W. K. Brown, 45 yrs old; Wife, 41 years old; Minnie, 2 years old.”

Every time I look at baby Minnie’s grumpy face I can imagine her thoughts: “I hate my dress! I hate my boots! I hate my spit curls! And you behind that big box on sticks—I. Hate. You. Too!”

I’ve looked to no avail for a Minnie Brown born between about 1848 and 1855. There are a few W. K. Browns and hundreds of W. Browns—William Browns, Wilhelm Browns, Walter Browns, Wilfred Browns, Wesley Browns—but none with a daughter named Minnie. If Mrs. Brown’s first name had been part of the inscription, I might have been able to suss out the family’s traces. Doing so may still be possible as more records come online. Until then, at least I can smile at eternally cranky Miss Minnie.

“Wife of Hugh Holmes” is written on reverse of this melancholy CDV. Assuming the heartbroken subject wore mourning for her spouse, I have looked into records of a number of men. The most promising was Hugh P. Holmes of Maine, who was born in 1833 and who died of Typhoid in August 1861, one month into his service with the 7th Regiment, Maine Volunteer Infantry. However, I can find no record of a marriage for this man. Hugh Holmes’s father filed a pension claim on his son many years later, but no widow is listed in the paperwork.

Another possibility is that Mrs. Holmes was not in mourning for her spouse, but for another close family member. This may indeed be more likely because Mrs. Holmes’s bonnet does not include white inner ruching signifying a widow. However, this practice was less common in the United States than in Great Britain. If this Mrs. Holmes did not mourn a spouse, it will be nearly impossible to identify her. Ω

A happy New Year, Gentle Readers. May 2017 be kind to all your clan!

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days of auld lang syne?

And days of auld lang syne, my dear,

And days of auld lang syne.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days of auld lang syne?

We twa hae run about the braes,

and pou’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fit,

sin’ auld lang syne.

And days of auld lang syne, my dear,

And days of auld lang syne.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days of auld lang syne?

We twa hae paidl’d in the burn,

frae morning sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d

sin’ auld lang syne.

And days of auld lang syne, my dear,

And days of auld lang syne.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

And days of auld lang syne?

And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere!

and gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak’ a right gude-willie waught,

for auld lang syne.

—1788 poem by Robert Burns set to the tune of a traditional folk song.

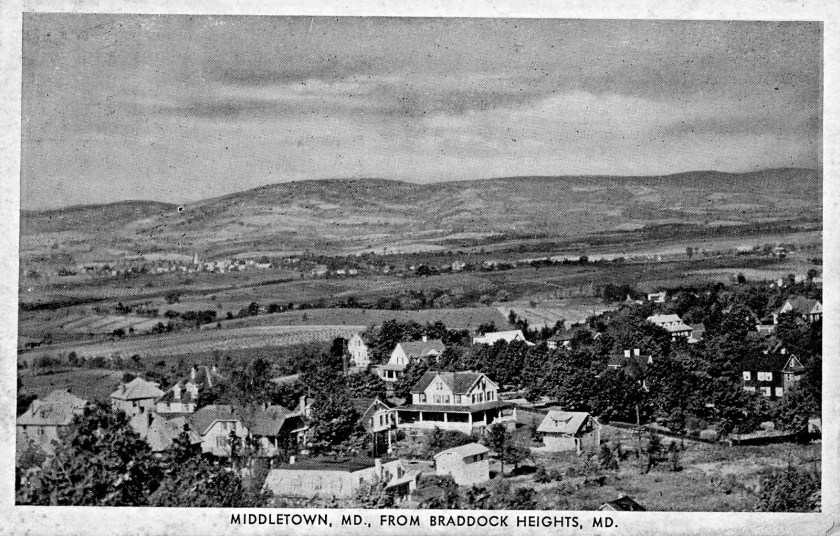

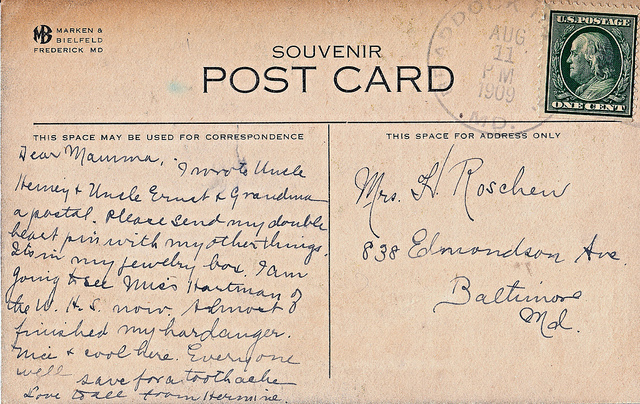

As a postscript, let’s return to the postcard’s message, in which Hermine Roschen mentioned a “Hardanger” that was nearly finished. This was a piece of Hardanger embroidery, or “Hardangersøm,” using white thread on white even-weave cloth, sometimes also known as “whitework” embroidery.

As a postscript, let’s return to the postcard’s message, in which Hermine Roschen mentioned a “Hardanger” that was nearly finished. This was a piece of Hardanger embroidery, or “Hardangersøm,” using white thread on white even-weave cloth, sometimes also known as “whitework” embroidery.