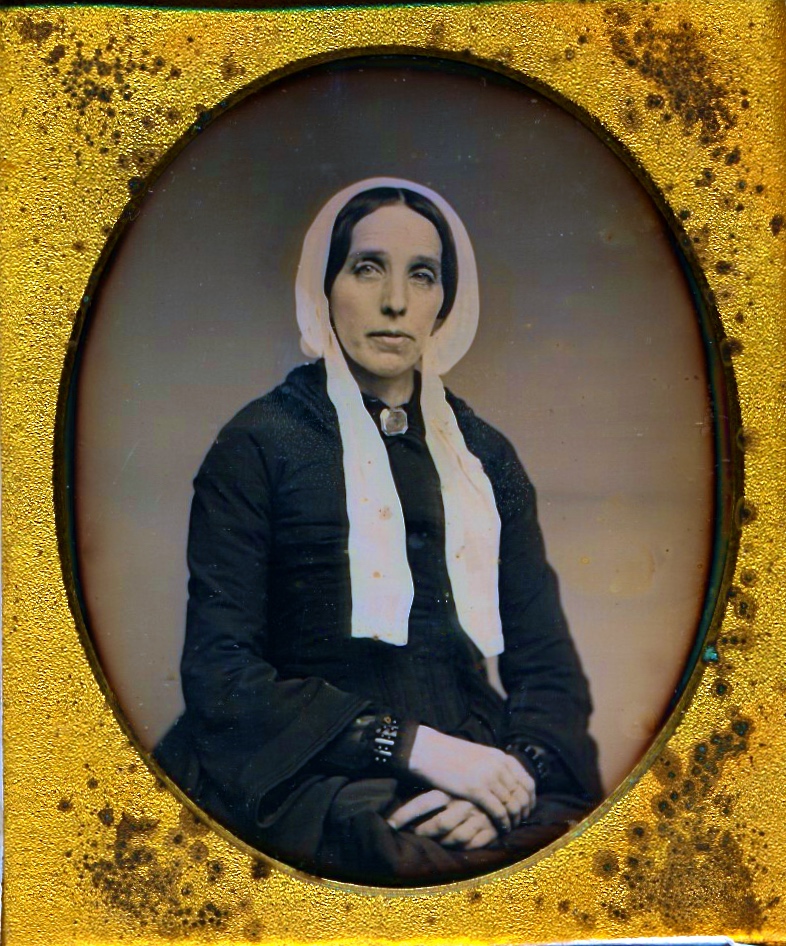

Agnes Warner Rider, pictured above, died on 16 May, 1901, at the age of 29. Presumably, her final words, as printed on this albumen carte de visite, were “I’m so tired. So tired!”

Agnes was born 18 January, 1872, in Southwark, London, to Charles Ryder (1846-1907), a printshop manager, and his wife Hannah Bramley (1847-1919), who both hailed from Loughborough, Leicestershire. Agnes, along with her other siblings, was baptised on 19 January, 1874, at Saint George the Martyr, Queen Square, Camden. At that time, her family lived at 10 Dunford Road, Holloway, London, in a small terraced home that still stands today.

The 1891 Census reveals that Agnes was the eldest surviving child in a family that included siblings Archie Hammond, Dudley Charles, Gertrude, Isabel, Henry Granville, Grace Hannah, and John Basil. Baptismal records indicate there was also a sister called Martha, born in 1878, one named Elizabeth Helen, born in 1868, and another called Marguerite, born in 1870. These three girls do not appear to have outlived childhood.

When the 1901 Census was taken, Agnes had but little time to live. She is listed as the eldest of a group of six children still in the home, along with Archie, Dudley, Henry, Grace, and John. One worked as a milliner, one as a dressmaker, and one as a merchant’s assistant. Archie had already married and become a young widower.

This census also reveals this clue as to why pretty, brown-eyed Agnes had not married or held a job: “Curvature of the spine since birth” was scribbled at the far right of the enumeration page.

In the Victorian era, spinal curvatures, like scoliosis and kyphosis, were prevalent. There were misconceptions about the causes of scoliosis, sometimes linking it to moral failings or perceived societal problems rather than solely medical conditions. Victorian attitudes toward spinal deformities reflected the broader societal views on disability, ranging from pity and fear to marginalization. Those with such conditions might be seen as “others” and face challenges in social and economic participation.

Treatment options for spinal curvature were varied and often experimental. Doctors utilized braces and modified corsets for correction. Traction and immobilization techniques were employed to reduce the curve, sometimes with limited success and potential complications, like paralysis.

In the mid-19th century, surgeons began exploring surgical options like percutaneous myotomies (muscle and tendon cutting) and later, spinal fusions to address deformities. However, these procedures carried significant risks, including infections and recurrence. Some practitioners advocated for gymnastic exercises to strengthen back muscles and treat deformities, believing it was more effective than solely relying on braces.

While spine curvature was not often fatal, it depends on severity and type. In severe cases, it can lead to respiratory complications, cardiovascular issues, nerve damage, reduced mobility, and significant pain. Some or all of these could lend weight to Agnes’s departing words, “I’m so tired….”

Agnes Warner Ryder was buried on 22 May, 1901, at Highgate Cemetery, Camden. Her grave, Square 19, Grave 33932, remains unmarked.

Ω