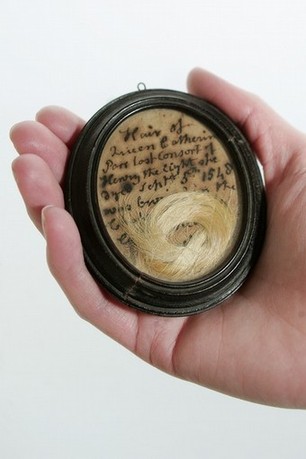

This piece from my collection is an antique English, 9-carat gold comet mourning pin. It is beautifully made, with a hand-chased stylized tail, black enamel embellishment, and a glittering foiled paste stone in silver settings, clearly displaying a black spot to simulate the open culet of a diamond.

The unusual shape of the brooch commemorates the return of Halley’s Comet in 1835. Although this piece neither contains a loved one’s hair nor bears an inscription, the use of black enamel almost certainly associates it with loss during the comet pass year.

Halley’s Comet is named after English astronomer Edmond Halley, who studied previous sightings and correctly predicted its 1758 apparition. The comet returns every 75 years, with its last apparition in 1986 and its next to come in 2061. I will be 98, if I live to see it.

The first report of the comet is from its pass above China in 467 B.C. (Centuries later, during another apparition, the Chinese would call it by the beautifully evocative name, “Broom Star.”) The British Museum, London, holds other documentation in the form of cuneiform tablets describing the comet’s appearance over Babylonia in late September, 164 B.C.

Continue reading “Comet Brooches: A Legacy of the 19th Century’s Sidereal Wanderers”