Augustus Frederick Snell was born 19 January, 1833. Almost a month later, on 17 February, 1833, he was christened at St. Michael, Headingley, West Yorkshire, England, which is today a suburb of Leeds. When Augustus was born, Headingley was still very much a village, but one that had begun to lure the affluent who wished to escape the industrial city’s smoke and bother.

Augustus’s parents, William (1791-1847) and Maria Calvert Snell (1803-1873), were respectable, educated late Georgians. On their marriage record of 9 July, 1825, William’s occupation was given as “professor of handwriting.” Later, he became a teacher of stenography and a shorthand writer for the company of Lewis & Snell on Board Lane, opposite Albion Street. The company’s advert in the 14 July, 1825, issue of the Leeds Intelligencer states that “the invaluable and delightful art of stenography, taught by the aid of mnemonics, in the most interesting and amusing manner, by which its principles may be indelibly fixed upon the most treacherous mind.” The price was 25s for the six lessons of the course, and separate apartments were set aside for ladies and those who wished to take their lessons alone.

Maria Calvert ran the Ladies’ Seminary in Headingley before her marriage, and after a brief honeymoon, reopened the school on 14 July, 1825. An Intelligencer advert that ran on that day noted the cost per student per annum as 20 Guineas, for which the girl would be instructed in reading, grammar, geography, plain and fancy needlework, writing, and arithmetic. Additionally, “Mrs. S. has made arrangements for instructing her Pupils in Music, Dancing, Drawing, and every fashionable Accomplishment.”

In future adverts, the school was described as “commodious, in a remarkably pleasant and airy situation, and has two playgrounds.”

In the years ahead, Maria advertised for male day students who would be instructed by William Snell. They needed increased income as babies began to arrive. The Snells produced eight children, most of whom survived childhood: William Mortimer (1826-1835), Adolphus (1828-1832), Maria Ruthetta (1831-1832), Augustus, Edmond Garforth (1834-1871), William (1837-1918), Walter (1838-1902), and Maria (1840-1898).

Another advertisement in the Leeds Mercury of 6 July, 1837, revealed the Snells were clearing out ahead of a move to London. Up for sale were “the household furniture; books; pictures; Mahogany dining, card, and Pembroke tables; carpets; sets of Moreen window curtains and appendages; looking glasses; camp bedsteads and hangings; feather and flock beds and bedding; cane seated chairs; chests of drawers; a small select library of books; Mahogany and painted press bedsteads; mirror, kitchen, and other requisite effects. In lots to suit purchasers, and without the least reserve.”

“Springing from his bed, he possessed himself of a pair of pistols, which with some difficulty were wrested from him.”

The great city of London was William Snell’s birthplace. His father, Augustus’s grandfather Richard Snell (1759-1831), operated canal carriers from the nation’s metropolis to Yorkshire, Manchester, Liverpool, and the north of England. According to the 20 December, 1819, Intelligencer, “Goods are daily forwarded per Fly-Boats, on the most approved System, with the utmost care and dispatch. Should the Canal Conveyance be stopped by Frost or Accident, Goods will be forwarded by Land, if required, at the lowest possible expense to the owners.” Those wishing to use these services were told to find Snell, Robins, and Snell of London at their warehouse, White Bear Yard, Basinghall Street. It also appears that the group kept the White Bear Inn, presumably also of that place.

Richard Snell died 18 January, 1831, in Edgeware Road, Paddington, leaving the majority of his estate to his son Adolphus, including all his wearing apparel, household furniture, utensils, wine, beer, liquor, and fuel. William Snell inherited 1/5th of his father’s estate, as did his other uncles—all of them colorful characters.

Take, for example, Richard Snell the younger (b. 1789) who died when Augustus was two. “MELANCHOLY OCCURRENCE!” screamed the Manchester Courier on 2 February, 1839. “We are sorry to announce the death of Mr. R. Snell, wine and spirit merchant…. He had been laboring under considerable mental irritability for some days, although free from violent or dangerous symptoms.” Whilst his doctor was with him one evening, “He was suddenly seized with an impression that his life was in danger. Springing from his bed, he possessed himself of a pair of pistols, which with some difficulty were wrested from him.”

After being pacified by his doctor and wife, Snell thought he heard the front door open. “He again became excited, rushed downstairs, and finding the door to the house locked, he seized a poker, broke the windows and succeeded in getting out into the yard. He thence crossed an orchard, and proceeded into Mr. Seddon’s premises adjoining, where he sank down exhausted,” reported the Courier. Shortly thereafter, his doctor found Snell “quite dead.” An inquest decided that “the deceased had died from the effect of excessive excitement, under the influence of temporary derangement.”

Another Uncle, George Blagrave Snell, was lauded in memoriam by the London Daily Telegraph after his sudden death from a heart attack in Brighton in 1874. Under the title “Death of a Well-Known Shorthand Writer,” it was reported, “Mr. Snell was the father of his profession, having followed it actively for upwards of a half century…. He was retained by the Government, often at much risk to his life, to report the speeches made by various agitators at public meetings during the time of the Irish Rebellion of 1831, and he was known at that time as ‘The Recording Angel of the Marquess of Anglesey’…. He has since on many important occasions been engaged by the Government, and his presence will not fail to be missed, not only in the courts of law, but in both Houses of Parliament.”

In the days before audio and film recording, shorthand writers like Snell played an important role in the workings of justice. It was their job to faithfully transcribe interviews with the various parties in court cases, civil and criminal. Traces of Snell’s normal daily work (when not busy in his superhero role of “Recording Angel”) can be found in the records of the Old Bailey, such as a case against one George Sherborne, who was charged with “Unlawfully within four months of his bankruptcy obtaining from Samuel Brewer and others certain pianos, and disposing of them otherwise than in the ordinary course of his trade,” which sounds ridiculous, and frankly was (the defendant was found not guilty), but shows how seriously bankruptcy was taken in Victorian Britain.

Snell describes his part of the process in the trial transcript, “I am one of the official shorthand writers to the London Court of Bankruptcy, and attended the examination of the prisoner on 15th January, 1879, before Mr. Registrar Pepys, and took down the questions put to him and his answers—the transcript on the file of proceedings is correct.”

George Blagrave Snell married at age 20 Harriet Saxon (1802-1885) on 15 January, 1825, at St. Marylebone, Westminster. Snell and his wife had eight children, all of whom lived to adulthood. One of their sons, for whom it is worth pausing, was Henry Saxon Snell (1831-1904). He was Augustus’s first cousin and became an architect of some note.

Henry Snell attended University College London and was inducted as a fellow into the Royal Institute of British Architects. He specialized in designing public buildings and amongst his works were the Montrose Asylum, the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, the Leancholi Hospital, and the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, Canada.

Another son, George Blagrave Snell, Jr. (1829-1910), also became a shorthand writer and his father’s business partner until the older man’s demise. His story shall be told farther along.

“I have a printing press and types for printing within Newcastle Place in the Parish of Paddington.”

When Augustus’s Uncle Adolphus Snell’s life ended on 6 September, 1872, he was a civil engineer’s clerk in Baker Street, but earlier, he was a printer. A surviving letter in the British National Archives of 5 April, 1834, to the Clerk of the Peace in the county of Middlesex reads, “I, Adolphus Snell, of 13 St. Alban’s Place, Edgeware Road, Paddington, do humbly declare that I have a printing press and types for printing…within Newcastle Place in the Parish of Paddington, for which I desire to be entered for that purpose in pursuance of an act passed in the 39th year of His Majesty George the Third, entitled ‘An Act for the More Effective Suppression of Societies Established for Seditious and Treasonable Purposes and for Better Preventing Treasonable and Seditious Practices.’”

(Inscrutably, Adolphus’s death certificate indicates that he expired of “disease of ankle & exhaustion” while at Westminster Hospital.)

Next we come to Augustus’s Uncle James Snell, born 13 March, 1798, in St. Marylebone, Paddington, London. His daughter Emma Harriet Norwood Snell was baptized 26 December, 1822, at Paddington, St. James. This church record notes the occupation of James Snell as dentist.

James Snell invented the first mechanical reclining dental chair with an adjustable seat and back in 1832. James Snell was also a member of the Royal College of Surgeons and the author of A Practical Guide to Operations on the Teeth, in which he made the design of his dental chair design public.

“There is no part of the apparatus of the dentist of more importance to his success, than a good operating chair. To this particular, the professors of this country have not paid sufficient attention, most of them having nothing but a common arm-chair, the use of which must, in many cases, be alike inconvenient to the operator, and fatiguing to the patient,” he wrote. “For some years I used nothing but a common arm chair, but I was so constantly encountering proofs of its inconvenience, both to myself and the patient, that I felt it my duty to construct a chair, better, adapted to the purpose. Having done so, I can say with sincerity, that I have never ceased to blame myself for having so long neglected it.”

At some point afterward, James Snell emigrated to the West Indies. He was memorialized in the London Standard of 9 August, 1850, in two simple lines: “On the 6th…at Kingston, St. Vincent’s, West Indies, James Snell, Esq., in this 55th year.”

Newcastle Place, as the Snells knew it, is long erased, but it was then and is today a literal stroll to Paddington Station.

It is unclear why the Snells left Headingley for London in 1837, but the relocation was likely tied to Uncle Adolphus’s press. When Augustus’s brother Walter was born 20 September, 1838, and christened on 3 November, the baptismal entry records that William and Maria lived in Bayswater and that William was a printer.

A decade after returning to London, Augustus’s father died 3 December, 1847. The 1851 Census placed the family in Paddington, living in 5a Newcastle Place, which was the site of Uncle Adolphus’s press. Maria Snell was the 67-year-old head of the house and business, with her was 18-year-old Augustus and others of his siblings, the eldest of which were working for the printery.

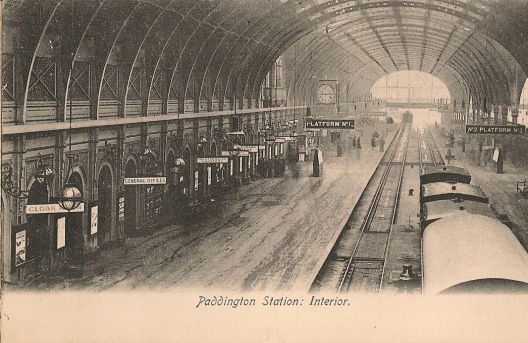

Newcastle Place, as the Snells knew it, is long erased, but it was then and is today a literal stroll to Paddington Station. Construction for the main terminal was completed and the facility opened to the public 29 May, 1854. Augustus would have seen and heard the trains toing and froing, and the seed was possibly placed in his mind that the railroad could provide meaningful work.

December, 1856, banns were read at St. Mary, Paddington Green, for Augustus and Jane Pullan, who was the wan, brown-haired, and dark-eyed daughter of Thomas and Ann Pullan. The marriage was solemnized 10 February, 1857, in the parish of St. Mary, Paddington Green, Westminster.

It is probable that the original daguerreotype of my cabinet card was made to commemorate the couple’s union, as the fashions worn by Augustus and Jane date exactly to their marriage year. Some time later, probably in the late 1880s or early 1890s, the daguerreotype was duplicated by the well-known “Stereoscopic Company of 110 & 108 Regent Street W.” (Visit the company’s website to see a stereoview of the building where a Snell clan member took the wedding daguerreotype to be copied.)

Jane’s father, Yorkshireman Thomas Pullan, born in 1803, was a mason by trade. Her mother, Anne Booth, was from Spofforth, Yorkshire, born circa 1807. Jane, the eldest daughter, was born in Chapel Allerton, West Yorkshire, sometime before 12 August, 1838, when her christening occurred at St. Mary the Virgin, Hunslet.

The Pullan family appears on the 1841 and 1851 censuses of Chapel Allerton. During the latter of these censuses, Jane, then aged 18, was enumerated as a house servant at the home of a Royal Bank of England clerk and his family. At some point before 1856, Jane left this employment and moved to London.

It may be that the Snells and the Pullans knew each other. Augustus’s childhood home of Headingley is a mere two miles from Jane’s Chapel Allerton. Perhaps the couple were long-time friends—even long-time sweethearts, or perhaps they met through a chance encounter in the capital city. Whatever the case, four years after their marriage, the 1861 Census placed Augustus and Jane Snell in Christchurch, St. Marylebone, Middlesex, living at 6 Sherborne Street with their sons Thomas Edmund (b. 4 January, 1858; baptized 7 March, Paddington Green) and Charles Walter (26 November, 1859, Marylebone, London). Augustus listed his occupation as a printer and their abode was in Grove Terrace.

Two years afterward, in February 1863, Augustus, then aged 29, became employed by the Great Western Railway in the goods department at Paddington Station. He stayed in the job only a month then resigned his position. Why he did so is not known, but Augustus never again attempted to make the railroad a career.

The 1871 Census enumerated the Snells in Willesden, Middlesex, in Northwest London, about five miles from Charing Cross. The area was mostly rural then and had a population of only some 18,500. But Willesden was on the cusp of urbanization. The Metropolitan Line’s stop at the Willesden Green connected it to the city center in 1879 and just 25 years later, the population grew more than seven times to 140,000.

In 1871, Augustus stated his occupation as a shorthand clerk, no doubt drawing on skills learned from his father. By 1881, Augustus worked as a solicitor’s clerk and both his sons were clerks in an insurance agency. The Snell family lived at East End Villa, on East End Road, Finchley, some six miles further northwest, where the population was less than 12,000.

Ten years later, in 1891, the couple had become what we now term “empty nesters,” who lived with a servant in a terrace house at 51 Weston Park, Hornsey, Middlesex, now part of Crouch End. Augustus again stated his occupation as shorthand clerk.

As the century came to the close, Augustus and Jane left Middlesex for retirement in a cottage in the Essex countryside. Augustus died 20 December, 1906. The probate record of his Will reads “Snell, Augustus Frederick of Fairview Cottage, Ashington, Rochford, Essex….Probate London, 28 January, to Jane Snell, widow. Effects £294 12s. 6d.” Jane lived until 5 July, 1911, also dying in Ashingdon.

The couple’s elder son, Thomas, spent his working life as an insurance clerk. He married Kate Strathon, who was born in about 1860 in Plymouth, Devon, and by her had two daughters: Dorothy Strathon (1892-1971) and Winifred Mary (1894-1972).

In 1891, Thomas and Kate lived at 3 Arthur Villas, Belle Vue Road, Friern Barnet, Middlesex, but by 1894 they moved to 77 Victoria Road, Stroud Green, Hornsey, near his parents. By 1901, Thomas and family lived in Walthamstow at 17 Avon Street; by 1911, after his parents’ deaths, the Snells moved to 71 Fishpond Road, Hitchin, Hertfordshire. Thomas died there 12 February, 1944. His will was probated at Llandudno to his nephew Edmund (see below) on 21 March of that year, with effects of £800 16s. 7p.

The Snell’s second son Charles married Lillian Helen Miller (1866-1892), the daughter of Henry Miller, on 2 May, 1891, at St. Peter, Hammersmith. They had a son, Edmund Norie Snell (1892-1984), whose birth appears to have caused his mother’s death. Charles married again at age 35, in 1894, on the Isle of Wight, to Agnes Jefferd. With her, he had two more children: Marjorie Norah Muriel (1895-1983) and William Frederick Aubrey (1899-1962). Charles eventually became an insurance broker and died in Saltford, Somerset, 27 April, 1920. His Will was probated on 9 July, with effects of £878 15s.

“The said Elizabeth Snell lived and cohabited and frequently committed adultery with the said George Blagrave Snell at No. 4 Grafton Road, Holloway in the county of Middlesex.”

Augustus’s younger brother, Walter Snell, married Elizabeth Colebrook (1843-1899) on 19 June, 1864, in St. Peters, Walworth, Surrey. She was the daughter of Thomas and Eleanor Colebrook—he, an omnibus conductor according to the 1851 Census of St. Mary Paddington; a butcher according to the 1861 Census of same; and a gentleman according to the couple’s marriage record.

For a time Walter and Elizabeth lived in Aberdeen Place, Maida Vale, then the 1871 Census placed them at 155 Holloway Road, Islington. Walter, aged 32, was an architect and surveyor. The couple had a daughter, Ellen Maria, born 13 December, 1867.

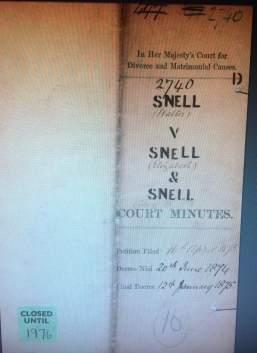

What happened next was told in Walter Snell’s solicitor’s words, delivered to Her Majesty’s Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes on 16 April, 1873: “On diverse occasions in the months of July, August, September, and October One Thousand Eight Hundred and Seventy Two, the said Elizabeth Snell committed adultery with the said George Blagrave Snell [Walter’s first cousin, the son of his eponymous uncle] at your petitioner’s residence No. 155 Holloway Road aforesaid. That in the month of October One Thousand Eight Hundred and Seventy Two, the said Elizabeth Snell lived and cohabited and frequently committed adultery with the said George Blagrave Snell at No. 4 Grafton Road, Seven Sisters Road, Holloway in the county of Middlesex.

“That from on or about the nineteenth of October…up to the date of this petition, the said Elizabeth Snell has lived and cohabited and frequently committed adultery with the said George Blagrave Snell at No. 10 Vorley Terrance, Junction Road, Highgate in the County of Middlesex.” The solicitors concluded, “Your petitioner claims from the said George Blagrave Snell as damages in respect of the said adultery the sum of one thousand pounds.”

The judge ordinary in this case, after hearing from counsel on both sides, made a decision that the case would go to trial so “that the questions of fact arising from the pleadings in this cause be tried…and the damages assessed by verdict of a Common Jury…and further ordered that the respondent and corespondent be at liberty to file their answers to the petition filed in this suit.”

The trial, with all the juicy detail it would have produced, appears never to have occurred. On 28 November, 1873, Walter Snell’s solicitors filed “draft questions and questions for the jury, set the cause down for the trial and filed notice.” Early the next year, on 5 February, the solicitors issued a subpoena ad testificandum (subpoena ad test), a court summons to appear and give oral testimony for use at a hearing or trial. Another subpoena was issued on 11 February. The next entry is for 9 June, when once again, a subpoena ad test was issued. About fortnight later, a decree nisi was made. The final divorce decree was issued 12 January, 1875.

George Blagrave Snell, Jr., was married when he began his affair with Elizabeth. Emily Maria Pile (1835-1917) had become his bride 23 years before, on 18 July, 1850. By 1873, they had six children living. After the divorce, the 1881 Census placed George and Elizabeth cohabitating as husband and wife in a respectable lodging house at 9 Cunningham Place, Marylebone, London, run by the daughters of Marmaduke R. Langdale, formerly of Madras, East Indies. Meanwhile, George’s legal wife, Emily Snell, was running a large boarding house at 32 Bedford Place, St. George, Bloomsbury. With her were two sons, Robert and Percy—the former a stock broker’s clerk and the latter a shorthand writer.

By 1891, Elizabeth Snell had taken over the Langdale’s Boarding house, but all was not well: Elizabeth was an alcoholic. She was either a drinker all along or became one after the divorce. Elizabeth died 6 January, 1899, in Saint Luke’s Hospital, Old Street, London, aged 54. The “wife of George Blagrove Snell…4 Portdown Road, Maida Vale,” expired of “alcoholic paralysis, heart failure confirmed by Wm. Rawes, Medical Superintendent, St. Luke’s,” stated her death certificate. (The term alcoholic paralysis covers a host of nervous system disorders directly resulting from the ingestion of toxic amounts of alcohol.)

Two years later, on 12 August, 1898, 69-year-old George had a daughter, Emma Florence Georgina Snell, by 20-year-old Emily Elizabeth Wright who hailed from Woolpit, Suffolk. They married 27 October, 1900, and lived in Fulham, London, in a small terrace house at 52 Harwood Road. George died on 31 October, 1910, aged 82, in Surrey. His small obituary read, in part, “Funeral to-day, 2.30, at Bramshott Cemetery. Friends kindly accept this, the only intimation.”

On 23 November, 1911, Emily gave a birth to son who she named Herbert John Anthony Snell. I cannot see a way, if the dates of George’s death and Herbert’s birth are correct, that he could have been Snell’s son. It appears that Herbert was sent to live at a Fegan’s Home for Boys and emigrated to Canada in the 1920s.

Walter Snell lived until 28 May, 1902, dying at Clarendon Lodge, Paignton, Devonshire, leaving his daughter Ellen £217 3s. 6d. She married brewery agent and widow William Parker Margetson 19 February, 1891. Although she had a number of stepchildren, Ellen gave her father but one grandchild, a son who grew up to be Major Sir Philip Margetson (1894-1985), assistant commissioner of Police of the Metropolis from 1946-1957. Ellen died on the Isle of Wight aged 92, on 31 March, 1962. Ω

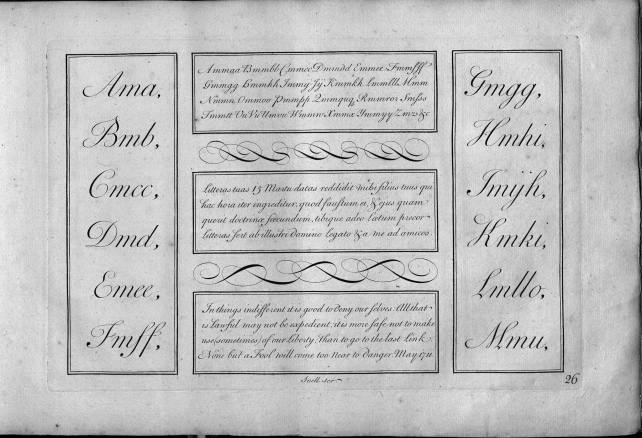

Although I do not believe the author is related to the above branch of the Snell family, I came across a 1712 book titled The Art of Writing in its Theory and Practice by Charles Snell. Snell was born in 1670 and died in 1733. A font named after Snell is still in use today. Above and below are several lovely pages from the book. More can be seen here.

Fascinating! How do you accumulate so much detail….?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It takes hours and hours of research and assembling across a lot of records platforms. (And speedy you, you read it before the copyedit was finished. I apologize for the mistakes that are now all gone. I hope.)

LikeLike

Very interesting lives.

LikeLike

I read this while I was in the airport waiting to fly to San Francisco on my way home from Hawaii (on the 19th, the day after you posted it), but was unable to comment on it at the time as Hawaiian Airlines does not have wi-fi on even their island to mainland flights and I forgot about it as the next day I was traveling as well. Anyway, this was a fascinating EPIC article about a family and the careers they had that helped them provide for their families over time. The fortunes of the family were often tragic, but still, to blend this all together and follow so many siblings and children over this period of time truly had to be a labor of love!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sim, I am just glad you read it at all! LOL. Our mutual love of history and genealogy is a blessing.

LikeLike

Emily Elizabeth Wright was my great grandmother and I have been tracing her relationship with George Blagrave Snell (Jr) for some time. I suspect the picture you have of her here may well have come from a source I have published online. To add to this article, please note that I have yet to find any proof that George was ever formally or legally married to Emily Pile. She was indeed married in 1850 but to another shorthand writer – Frederick Cape, with whom she had a daughter. Emily’s sister Caroline then married George’s brother Henry (the notable architect). I believe it was probably at this event that George and Emily first met. George and Emily then lived together with George giving Emily’s daughter his name, but ‘uncle’ Fred continued to visit. George Junior appears to have had a history of bankruptcy and infidelity. I don’t think my great grandmother hailing from rural Suffolk, had any idea what a family she was getting into when she married George (50 years her senior). If you have any further information about George Junior I would be very interested to share information with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this information, Dawn. I will update the story as soon as I can.

LikeLike

What a wonderful article Ann, and I’d love to talk more with about this family, as I can link in to Mary Ann Snell, daughter of Richard Snell and Mary Maynard. Mary Ann went on to marry a John Robins, another Canal boat carrier, and I can fill you in on them if you weren’t aware already. Pls drop me a line to follow this, to: nigel.crisp@gmail.com

LikeLike