On September 10, 1862, a detachment of Confederate cavalry rode into Middletown, Frederick County, Maryland, led by their captain—a town native son—to search out an American flag. It was there as reported, suspended from the porch of a Main Street home and floating prettily in the breeze. Incensed, looking to fight, and not knowing the battle horrors that the next days would bring, some dozen of the cavalrymen dismounted and rushed up the steps to tear Old Glory down. But a proud seventeen-year-old stepped outside to confront them.

For her patriotism during that tumultuous week, teenager Nancy H. Crouse, known to her loved ones as Nannie, was hailed for a time as “Middletown’s Maid” or, later, “Middletown’s Barbara Fritchie.” But now her story molders in obscurity, even in her childhood hometown.

Her father, George William Crouse (1804-1892), came from Waynesboro, Franklin County, Pennsylvania—the son of Hessian immigrant Johann Phillip Krauss and his wife Anna Marie Eberhardt; Nannie’s mother, Catherine Ellen Smith (1814-1862), was a native of Leesburg, Virginia. George Crouse was a saddler and harness maker—the trade he pursued his whole life according to censuses, as did his own father and his eldest son.

George and Catherine were early members of the Church of the Latter Day Saints. Mormon missionaries Jedediah M. Grant, Erastus Snow, William Bosley, and John F. Wakefield came to Maryland in 1837. Snow and Bosley recruited new members in Washington County, where they organized a Mormon branch. Snow preached in Greencastle, Pennsylvania, and was reported to have baptized more than a dozen new Saints in Leitersburg, just south of the Pennsylvania line. It is likely that George Crouse was one of either of these groups of converts.

The Latter Day Saints, following their prophet Joseph Smith, settled in the mostly abandoned town of Commerce, Illinois, in 1839, renaming it Nauvoo and building a community of as many as 20,000. The Crouses, who were then parents to George V., born in 1834; Mary Ellen, born in 1835; Phoebe Ann, born in 1838; and Catherine J., born in 1840, were in Nauvoo at the birth of daughter Laura in May 1841. The family was listed in the Nauvoo Stake Ward Census of 1842, bought property there in April, and Catherine was accepted as a member of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo on 28 September. On 9 March, 1844, George Crouse, who was by then a Mormon elder, fronted a petition to lengthen a street in the town.

Just a few months later, on 27 June, the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother were murdered by a mob while imprisoned in Carthage, Illinois. Even before their deaths, a leadership void opened and schisms cleaved. Crouse was excommunicated on 15 September, 1844, for “unchristian conduct.” (It is likely this happened because he wasn’t among the clique who’d grasped power, rather than for any offense he committed.) Catherine was heavily pregnant so the Crouses remained in Nauvoo for Nannie’s birth on 16 December. After Catherine and the baby could safely travel, the Crouses went east to Pittsburgh—part of the way by steamboat, as daughter Laura Crouse Cook recalled—where the family remained for several years.

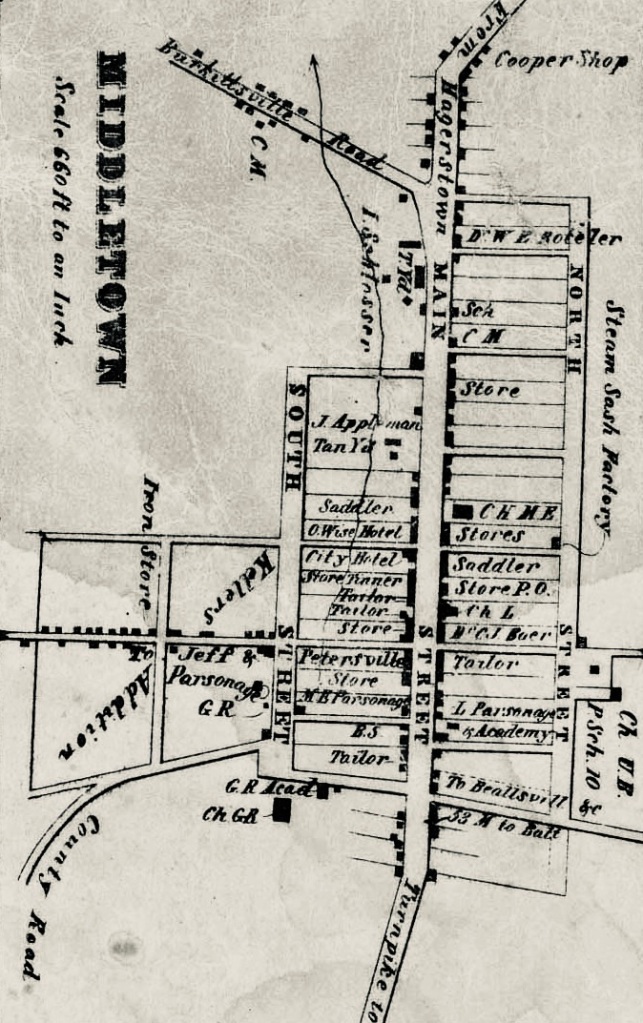

The couple’s next child, Martha Rebecca, was born 27 July, 1846, either in Pittsburg or her father’s hometown of Waynesboro, just over the Maryland line. The 1850 census reveals the family were in Middletown, and George Crouse would ply his trade there with the help of his namesake son until around 1880. There are several sources that say Crouse was a baker and confectioner, and these side professions may also be valid, but the evidence does not appear on official documents such as the censuses, where occupations are noted.

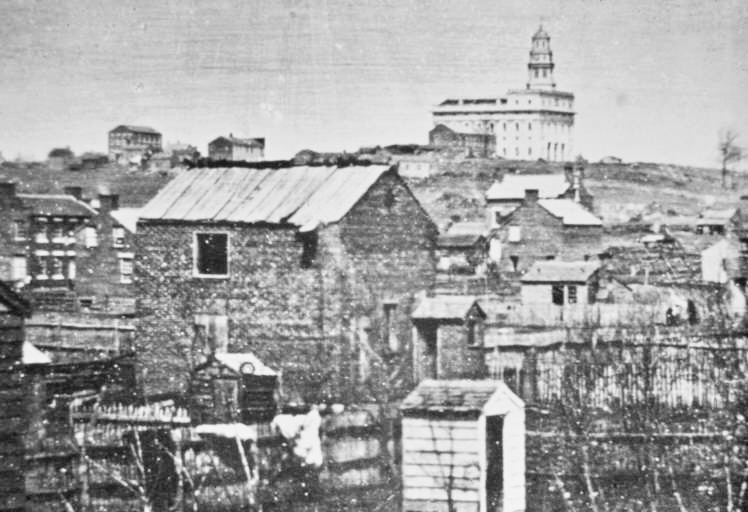

Nannie and her little siblings (Rebecca; Charles Melvin, born in 1853; and Frances Ida born in 1856) knew no other home than Middletown, nestled in the green valley surrounded by a checkerboard of agricultural fields and pastures; its streets, if not literally bustling, saw much commerce and many travelers. Nannie would have grown there, played there, been schooled there; however, as there is some evidence that George Crouse continued to identify as a Mormon, whether the family partook in Middletown’s hearty Christian religious life is unknown.

Nannie’s older sister Laura, who later lived in Frederick and who spoke to the Frederick News in April 1922, aged 81, did not mention the family’s Nauvoo experience in her childhood recollections, which could be telling. The faith that other members of the Crouse family embraced may be best evinced by their burials in Middletown’s Lutheran Church cemetery.

The Middletown Valley was of overwhelming Union sympathy. In January 1861, Myersville held a large pro-Union gathering at which speeches were made and resolutions passed. In February, Middletown held its own, and the Crouses were no doubt in the crowd of up to 3,000 people. After speechifying and adopting antisecessionist resolves, a 102-foot liberty pole was raised while the Boliver Band played a patriotic tune.

“On the whole, it was a day long to be remembered by those present, every one of whom seemed to partake of the general feeling of patriotism, clearly demonstrated that the citizens of our lovely valley, …with few exceptions, are loyal and devoted friends of the Union AS IT IS,” the 1 March, 1861, issue of the Middletown Valley Register proclaimed.

By all accounts, Nannie’s father was a warm Union man. Seeing the streets of Middletown congested with carriages, horses, and wagons, while men, women, and children wore their Sunday best, George Crouse must have felt the North’s cause was manifestly just and that any battles would be waged down South; their own small town was safe from harm.

⌘︎⌘︎⌘︎

Nannie Crouse’s story (and that of Mary Quantrell, detailed below) stands on more solid ground than that of Barbara Hauer Fritchie, who gained international fame through an ode by poet John Greenleaf Whittier. Whittier portrayed the nonagenarian Frederick denizen as defiantly shaking a Union flag at the troops of Confederate General J. E. B. Stuart from her second-floor window as they marched through the city in the lead-up to the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. When confronted and told to throw down her banner, the poem gives her tart, chin-lifted reply: “‘Shoot, if you must, this old gray head, But spare your country’s flag!’ [She said.]”

Whether Fritchie took on the Confederacy from the upper floor of her modest Patrick Street home was debated from the poem’s first printing in the October 1863 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. Fritchie was notably elderly (she was born in 1766, making her 95 in September 1862) and was mostly confined to her bed.

However, according to Julia Maria Hanshew Abbott (1839-1923), Fritchie’s great-niece, who was quoted in the essay “The Historical Basis of Whittier’s Barbara Frietchie” by George O. Seilheimer in 1884’s Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. II, “[Gen. Stonewall] Jackson and his men had been in Frederick and had left a short time before… Mother said I should go and see aunt and tell her not to be frightened… When I reached aunt’s place she knew as much as I did about matters, and cousin Harriet was with her. They were on the front porch and aunt was leaning on the cane she always carried. When the troops marched along, aunt waved her hand, and cheer after cheer went up from the men. Some even ran into the yard. ‘God bless you, old lady.’ ‘Let me take you by the hand.’ ‘May you live long, you dear old soul!’ cried one after another….”

At this point, cousin Harriet decided to retrieve for Fritchie a flag that was hidden in the family Bible. “Then [Fritchie] waved the flag to the men and they cheered her as they went by,” Abbott attested. She would eventually inherit the small, silk, 34-starred flag and show it proudly.

The genuine flag-waver in Frederick City was Mary Ann Sands Quantrell (1825-1879). She also lived on Patrick Street, reportedly only a block or so away from Fritchie.

This account of that day was supplied by Quantrell’s son-in-law, Joseph Walker, in early 1885 to a special correspondent of the Baltimore American, and carried by newspapers around the country as far afield as the Santa Barbara (CA) Daily Press.

“Mrs. Mary A. Quantrell was at that time a woman of [38], black-haired, and though she did become my mother-in-law afterward, I must say that she was very pretty. Her husband was then at work as a compositor on the National Intelligencer, in [Washington, D.C.], and Mrs. Quantrell was living in Frederick with her children,'” reported the Indianapolis Journal.

Mary’s kin, the Sands, were a well-connected and well-thought-of pro-Union family. “Mrs. Quantrell was for several years a teacher in Frederick and was a lady of unusual accomplishments. She was a frequent contributor to the press, the York (Pa.) Evening Herald, having printed many of her poems and other literary efforts… [Her] brother, George W. Sands, was a member of the Maryland legislature, and a United States collector of internal revenue by appointment of President Lincoln,” the News reporter noted.

Mary’s father-in-law was Capt. Thomas Quantrell (1785-1862) of the War of 1812’s “Homespun Volunteers,” and a native of Hagerstown, whose son Archibald Ritchey Quantrell (1816–1883) was her spouse. Captain Quantrell was an avid Unionist, despite being a slaveholder. Another near branch of the Captain’s family spawned William Clarke Quantrell (1837–1865) of Quantrell’s Raiders, a notorious Confederate guerilla unit.

“On the day that Jackson and his army passed through Frederick, [Mary] and her little daughter, Virgie Quantrell… were standing at the gate. They had several small Union flags, which they brought there to wave as the Confederates marched by. Mrs. Quantrell was enthusiastically loyal, and she, womanlike, simply took advantage of the occasion to show her devotion to the Union.

“They stood within a few feet of the line of march. Virgie was waving a very small flag, such as children play with on patriotic days. Many of the rebel soldiers had called out, ‘Throw down that flag!’ but the little girl kept waving it. Suddenly, a lieutenant drew his sword and cut the staff in two, the flag falling to the ground. The little girl then took another small flag and waved it, and this in turn was cut from her hand.

“Then Mrs. Quantrell displayed a larger flag and waved it in a conspicuous manner. This she continued to do until Stonewall Jackson and his men had all marched past her house. She was not molested in the least. In fact, many of the officers and men treated her with marked courtesy. Some of the officers raised their hats and said: ‘To you, madam; not to your flag.'”

Walker also told the reporter that “the Quantrell family are now in possession of three letters from [poet John Greenleaf] Whittier acknowledging his mistake and the injustice that had been done the real heroine, or rather the two heroines, as it would seem that the little Virgie was as much entitled to a niche in the temple of fame as her patriotic mother.”

Virginia May Quantrell was born in March 1862, making her about six months old in that September, so Walker was wrong: Virgie was not the child waving her flag beside her mother that day. The honor must fall on Julie Milton Quantrell, born in 1859, who would have been aged three, and therefore capable of standing.

According to her son-in-law, Whittier’s admission that he was misinformed about the identity of Frederick’s flag-waver combined with the claim that it was too late to change the famous poem seemed a personal slight to Mary Quantrell. “She was proud and ambitious, just the sort of woman who yearned for the glory of posthumous fame,” he opined.

In February 1869, Mary wrote to the Washington Star, laying out her story: Whilst she stood on her porch, a subordinate officer shouted a slander against the flag. “It was too much. My little daughter, who had been enjoying her flag secretly, at this moment came to the door, and taking it from her hand, I held it firmly in my own, but not a word was spoken. Soon, a splendid carriage, accompanied by elegantly mounted officers, approached. As they came near the house they caught a glimpse of my flag and exclaimed ‘See! See! The flag! The Stars and Stripes!'”

When the carriage—presumably Gen. Robert E. Lee’s—halted, a fearful friend told Mary to run away, but she refused. When an adjutant approached and demanded the flag, she also refused, telling him, “I think it worthy of a better cause.”

“Come down South and we will show you whole negro brigades equipped for the service of the United States,” he told her.

“I’m informed on that topic,” Mary retorted.

After this, the officer drew a sword and snapped the flag’s staff close to Mary’s hand, causing a loud report, then picked up her fallen flag and tore it to bits. “I pronounced it the act of a coward. Among the young ladies present was Miss Mary Hopewood, daughter of a well-known Union citizen of Frederick. Seeing my flag cut down, she drew a concealed flaglet from her sleeve… In an instant the second flag was cut down by the same man,” Mary wrote. An older officer then appeared, reproved the adjutant loudly, and dragged him away.

The article concluded by noting that it was through error “Mary Quantrell lost her everlasting fame, which was bestowed upon a bedridden old lady who never lived to appreciate fully the important place her name was destined to take.”

⌘︎⌘︎⌘︎

Early on the same day that Mary Quantrell cooly faced the ire of Lee’s adjutant, Nannie Crouse hung her flag from the porch of her family’s Main Street home. Not all of Middletown’s citizens were Union supporters. The Crouse’s nearby neighbor, hotel manager Samuel D. Riddlemoser (1811-1864) was “a man of Southern proclivities… and he frequently taunted Miss Crouse, telling her that her ‘rag’ would come down,” reported the Middletown Valley Register of 28 February, 1908.

Riddlemoser was a distinctly unlikeable fellow. Nannie’s brother Charles told the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune of 10 November, 1901, that Riddlemoser “openly and daily taunted his sister whenever he saw her, particularly when she would fling to the breeze… her big flag. Lee was marching northward, fresh from the victory at Chancellorsville. Rumors of all kinds were current as to our fate if the rebels invaded Maryland, and for this reason alone, we did not lay violent hands on our loud-talking neighbor,” whom the Crouses believed was a spy in communication with the scouts of Stonewall Jackson.

Charles himself encountered the general on the road when returning from a grist mill with a friend. Jackson was polite, Charles said. “He asked me several questions concerning Middletown and the roads thereabouts… On leaving us, he asked if there were any Yankees about. ‘You’ll find plenty of them if you go far enough,’ I replied boldly, though with considerable trepidation for the consequence.” Jackson merely smiled and rode away.

“The next day, a detachment of cavalry galloped into town, no doubt at the instigation of our neighbor, to secure the offending flag, which was floating as big as life in the wind,” Charles stated. He told the Tribune that the 30-strong detachment was “Louisiana Tigers,” as 9th Louisiana Infantrymen were known; however, the Middletown Valley Register, as cited in the Frederick News‘s 11 December, 1901 article, reported that these were “Virginia soldiers under the command of Captain Edward Motter [(1832-1893)], youngest son of… John S. Motter [(1800-1883)], who formerly resided at [Fountaindale Farm], east of town.”

The Motters were tavern keepers (their tavern still stands at the intersection of the Old National Pike and Hollow Road), farmers, and slaveholders—they owned six human beings in 1840, three in 1850, and four again in 1860, according to U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedules. Edward Motter attended the University of Maryland and earned a doctorate in medicine. He had a practice in Easton, Kansas, in 1854, where he intervened in an election dispute that turned violent; then he was back in Maryland in 1857, marrying Mary Amelia Brengle of Frederick. The couple made a home in Marion, Virginia, where Motter took up his practice once more.

Motter chose to fight for the Confederacy (his military records are lost); however, in a classic example of how the war split border-state families, his brother William Motter (1844-1915) was a Union sergeant in Company A, 65th Illinois Infantry. Edward Motter lost his 24-year-old wife in February 1863, and after the war, he drifted west with the Confederate diaspora, dying in Pulaski County, Arkansas, in 1893.

An unnamed Middletown citizen, who stood somewhere nearby when Motter and his men arrived at the Crouse home, later wrote down what he recalled of the incident. Charles Crouse possessed a copy of this account and quoted from it during his interview with the Tribune. The witness remembered the detachment galloping down Main Street and past the waving flag. Someone called, “Halt!” and the soldiers dismounted and rushed up the porch steps when next occurred “the bravest and most thrilling dramatic scene” he ever witnessed.

The unknown witness told his tale with the language of a bodice ripper. “A beautiful young lady, superbly formed, stepped from the doorway of her father’s house and demanded of the rebels what they wanted there. ‘That dammed Yankee rag!’ said a big ruffian trooper, pointing derisively to ‘Old Glory” and moving toward the door as though he would enter the house and tear it from its staff. Anticipating the rebel’s intention and taunting him with disloyalty to his country, Miss Crouse sprang past the man, ran up the [interior] stairway, hauled down the flag, and draping it about her form, returned to the porch, looking the very impersonation of the Goddess of Liberty.'”

The Confederate again demanded the flag but she looked upon him with disdain. Reportedly (and terrifyingly), he drew his revolver and pointed it at her head. Her little brother Charles, who was behind her, said he watched while cowering against an interior wall as other soldiers urged their companion to kill his sister.

The witness and Charles both recalled they heard Nannie say in a strong, firm voice, “You may shoot me, but never will I willingly give up my country’s flag into the hands of traitors.”

At this point, a more rational soldier told Nannie reassuringly, “They dare not hurt you or touch the flag while you have it round you, but please save the trouble and give it to [Captain Motter].”

Charles recalled, “Finally, seeing odds were against her and to hold out longer was in vain, she handed the beloved flag over to the captain, who left the house, tied the flag about his horses’ neck, and departed.” The squad rode back over Braddock Mountain to the Old White House, a tavern run by John Hagan, whose name by which the building is now known.

They were raising glasses to their victory when apprehended by Captain Charles H. Russell (1827-1895), who was known as the “Fighting Parson,” formerly a minister in Williamsport. Russell commanded a company of the 1st Maryland Cavalry. He and his men “came out a mountain road a short distance below Hagan’s… and captured every man except Motter, who, being acquainted with the country, slipped out a back door and escaped to the mountain,” reported the Frederick News.

According to Laura Crouse Cook’s interview with the Frederick News, Russell brought the captured Confederates back to the Crouse home, presumably to return the flag. The family kindly fed the prisoners and Mrs. Crouse gave Capt. Russell another Union banner that the family owned.

Nannie’s act, news of which quickly raced around Middletown, likely emboldened other young women. When Stonewall Jackson himself rode through the town soon thereafter, Henry Kyd Douglas (1838-1903) of the Confederate Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, who served on Jackson’s staff and later wrote of his war experience in I Rode with Stonewall, noted, “Two very pretty girls with ribbons of red, white, and blue in their hair and small Union flags in their hands ran out to the curbstone, and laughingly waved their colors defiantly in the face of the General. He bowed and lifted his cap with a quiet smile and said to his staff, ‘We evidently have no friends in this town.'”

⌘︎⌘︎⌘︎

In late September, Catherine Crouse experienced the first signs of an unidentified illness that would kill her. She lived her final days in a town traumatized by blood-drenched battles and overburdened with wounded troops from both sides. The church across from the Crouse home was crammed with injured soldiers brought over the mountain by a stream of army ambulances. As she sickened and took to her bed, Catherine heard the cries of those shot, maimed, and dying; the clomping horses’ hooves and thuds of boots; the shouted orders of doctors and surgeons; and the anxious voices of Middletown’s women who were actively caring for the invalids. Catherine passed away on 30 September.

It was through this continuing altered reality that Catherine’s casket was borne from the family home by George Crouse and male friends of the family, then the pallbearers and mourners took the slow walk to the cemetery where Catherine was laid to rest.

In 1854, Nannie’s brother George married and began a family with Malinda Lorentz (1837-1890), a daughter of one of Middletown’s shoemaking and tailoring multigenerational mercantiles. He joined Co. G, 7th Maryland Infantry as a drummer on 14 August, mustering a little more than a month before his mother died. It may have been in the army that he met John Henry Bennett (1841-1920), son of Frederick City’s Lewis Henry Bennett (1818-1898) and Mary Ann Margaret Suman (1821-1873). Bennett mustered into the 7th’s Co. E. on 31 August. Both men mustered out on 31 May, 1865, from Washington, D.C., and it is tempting to think they traveled home together.

However it was that the Crouses and Bennetts first met, Nannie married John Henry on 9 September, 1863, in Frederick. They would take up homemaking at 24 West South Street and John Henry would make a living as a wheelwright. The marriage produced seven children: Carrie Elner (1864-1905), Henry Luther (1868-1950), Robert Alton (1870-1950), Annie May (1872-1935), Jessie (1875-1951), Lewis William (1878-1949), and Norma (1881-1937).

When her brother Charles spoke to the Tribune in 1901, he supplied the newspaper with the only known image of his sister. The cabinet card photo, taken in the mid to late 1890s, shows Nannie in her fifties and proves that the description of her fresh beauty in September 1862 was not hyperbole.

By 1906, Nannie was ill with liver cancer, which caused her death on 22 February, 1908, aged 63. After a service held in the family home on West South Street, the coffin was carried away by six of her nephews acting as pallbearers. She was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

At the time of Nannie’s death, the Valley Register and Frederick News included the tale of that September day as part of her obituary and also printed a poem by author and native son Thomas Chalmers Harbaugh.

“Middletown remembers yet

How the tide of war was stayed,

And the years will not forget

Nancy Crouse, the Valley Maid.”

Ω