Ω

A selection of unidentified daguerreotype and ambrotype portraits.

Ω

“In terms of symbolism, the loss of the soul is the same as that of the body, representing a crossing over to a place that we do not know or understand.”

This unusual mourning brooch, which dates to between 1830 and 1840, is a late example of the sepia painting technique popular up to a century earlier. Sepia miniatures in the neoclassical style, such as the one below right, were painted with dissolved human hair on ivory tablets and typically feature weeping women and willows, funeral urns, graves, and other scenes and symbols of loss.

This brooch is dedicated by reverse inscription to “M. Thayer,” but little more can be known about the deceased, as the inscription includes no dates of birth or death. Thayer was likely occupationally connected to the sea, although the image may be wholly allegorical. A ship sailing toward a distant safe haven, accompanied or guided by birds, may be read as the soul journeying toward the afterlife in the company of angelic beings.

“What makes photography a strange invention is that its primary raw materials are light and time.”—John Berger

James Morley writes of this ambrotype of Channon Post Office & Stationers, Brompton Road, London, circa 1877: “I have found historical records including newspapers, electoral rolls, and street directories that give Thomas Samuel Channon at a few addresses around Brompton Road, most notably 96 and 100 Brompton Road. These date from 1855 until early into the 20th century. These addresses would appear to have been immediately opposite Harrods department store.”

The limited research I have done on this image, which is a stereoview card marked “State Block, New Hampshire, W.G.C. Kimball, Photographer,” leads me to believe it shows mourners of Concord, New Hampshire native Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804–October 8, 1869), 14th President of the United States (1853–1857).

The banners affixed to the carriage read “We miss him most who knew him best” and “We mourn his loss,” as well as another phrase that ends in the word “forget.” The image also features an upside-down American flag with thirteen stars.

This mid-1850s, whole-plate daguerreotype of a woman and three children is from the collection of Beverly Wilgus, another of the antique photo collectors of Flickr who has graciously allowed me to present her images. Of it, she writes, “[W]e have had the glass replaced by a conservator. It is our only whole plate daguerreotype (6 ½” X 8 ½”), which is the largest size that was in common production…. I have been asked why there is not father with the family. While it is possible that the father is deceased, I like to think that the photograph was a gift for him.”

If this image was a gift for Father, it was almost certainly purposefully posed to remind him, or any viewer, of his absence—the blank space in the middle the group screams to be filled. It is reminiscent of the portrait of the Bronte sisters, now known as the “Pillar Portrait,” which hangs in the National Gallery in London.

Painted in 1834 by the sisters’ talented, ego-driven, and alcohol-fueled brother who was then attempting to become a portrait artist, Branwell Bronte chose to eliminate himself and insert a column instead. It has been argued that he felt the composition was too crowded or that it was done in high dudgeon—we may never know which for sure. Charlotte died in 1855, at about the same time as Beverly’s daguerreotype was taken. After the death of Charlotte’s father in 1861, her husband, the Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls, cut the painting from its frame, folded it up, and took it with him to his native Ireland, where it languished for many years. During that time, the “ghost” of Branwell began to appear through the paint—part spectral bogeyman, part prodigal son.

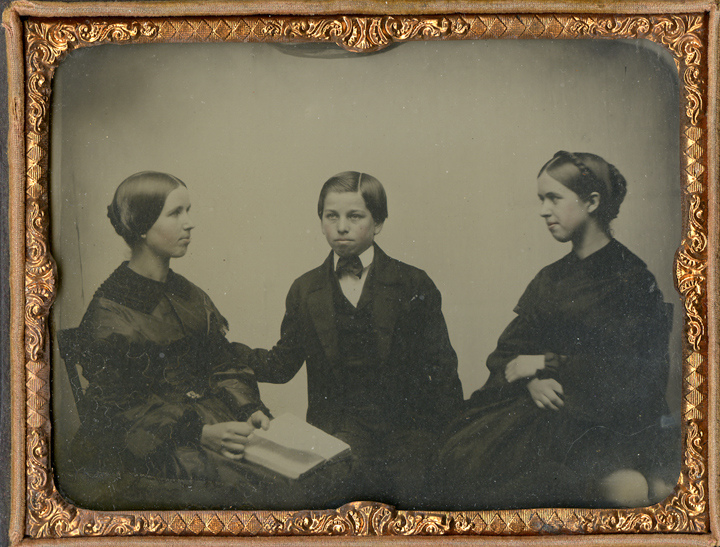

Another of Beverly’s images—this one an ambrotype also taken in the mid-1850s—again makes use of empty space to convey the message of loss. And in this image, it is indisputably death that has struck twice, leaving two pointed shapes like stab wounds between the three young people. A “reader” of this portrait, and it was yet very much a time of encoded meanings in art and photography, would know immediately that the teenage girls wore mourning gowns: the dark, wide lace collars of their dresses leave no doubt that the entirety of their costume is black. Between them is their younger brother, now the man of the family, reassuringly touching his elder sister’s arm. He seems stoic but unprepared for the task.

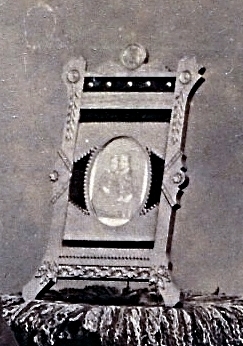

This final image used props to fill the void caused by death. Whilst the husband and wife focused on a point stage left (she almost certainly dressed in mourning), between them sat a plant stand covered by what must have been a colorful, almost childish string doily, upon which an elaborate picture frame was placed. It contains an image a girl and possibly a boy. The message can be taken no other way: “These were our children; now they are no more.” Ω

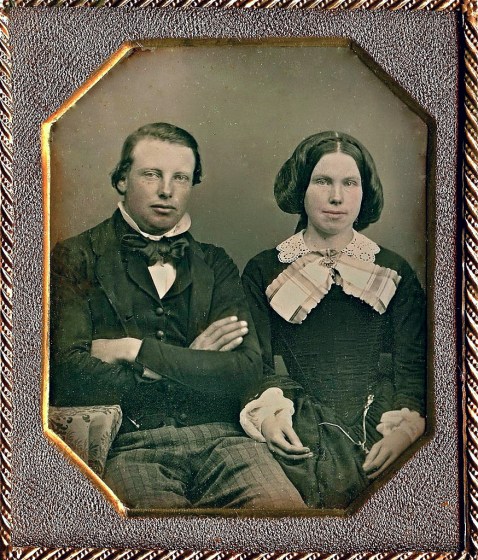

“Almost certainly a wedding portrait, this is a reasonably well-to-do couple, since they are dressed in formal day wear.”

This is another of my daguerreotypes, formerly of the Ralph Bova collection, which was published in Joan Severa’s My Likeness Taken. Severa wrote of the image: “Almost certainly a wedding portrait, this is a reasonably well-to-do couple, since they are dressed in formal day wear.

“The wife has done her hair in the bandeau style, in the longer, deeper roll that was one of the choices at mid-decade. Her hairdo is finished with ribbon ends hanging from a bow at the back of the crown. She wears what is probably a black velvet bodice over a black silk shirt. The fine whitework collar is large, and the white undersleeve cuffs are deeply frilled. The unusually wide silk ribbon is an expensive luxury; it flares prettily from the folds under the collar to spread over the bosom. A gold chain for a pencil hangs at the waistline.

“The young man wears a morning suit: a cutaway coat over striped trousers. His black vest matches the coat, and the high, standing collar of his starched shirt is held by a wide, horizontal necktie.”

When I first uploaded this image to my photostream at Flickr, a number of commentors suggested the sitters were siblings rather than man and wife. I agree there is a definite resemblance. Severna felt strongly that this image had the hallmarks of a wedding photograph and I also agree with her assessment. The two positions may be reconciled if the subjects are married cousins—a common occurrence until the second half of the 20th Century. Ω

Clearly, I had to win the auction—the wishes of Mr. Guppy, whoever he had been, seemed evident.

In July 2013, I purchased this carte de visite (CDV), which I recognized as an 1860s copy of an earlier daguerreotype. The subject reminded me of the English actor Burn Gorman in his role as Mr. Guppy in the 2005 BBC adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House. There was no inscription to identify the sitter, so in my Flickr photostream I titled the image “Mr. Guppy” and went on.

In January 2014, I stumbled across the auction of a 1/4-plate daguerreotype that left me gobsmacked. It was Mr. Guppy. The original image.

A conversation with the seller elucidated that the daguerreotype came from a Vermont estate, but there had been no accompanying CDV. The seller was equally surprised at the strange twist of fate.

Clearly, I had to win the auction—the wishes of Mr. Guppy, whoever he had been, seemed evident. I did not fail him; today, the daguerreotype and CDV are united in my care.

The daguerreotype’s brass mat is stamped “Jaquith, 98 Broadway.” According to Craig’s Daguerreian Registry, this was the gallery of Nathaniel Jaquith, who was active from 1848 to 1857 at that address.

Nathaniel Crosby Jaquith was born 30 April, 1816, in Medford, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, and died 24 June, 1879, in Elizabeth, Union County, New Jersey. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York. Jaquith was the brother-in-law Henry Earle Insley, also a daguerreian photographer, and he was the grandson of Nathan Jaquith, a private in Captain Timothy Walker’s Company, Colonel Greene’s Regiment, during the American Revolution, and the great-grandson of Benjamin Jaquith, who was also a private in that unit. Before taking up the new art of daguerrotyping in 1841, Jaquith operated a shop at 235 Greenwich Street, New York City, where he sold “Cheap and Fashionable Goods.”

When I received the daguerreotype, I found the image packet had old seals, but there were wipe marks on the plate. My supposition is that whoever wanted the daguerreotype duplicated handed it to the copyist, who broke the original seals and removed the metal plate from the packet, as the CDV shows the tarnish halo surrounding the sitter. The copyist may also have cleaned tarnish that had developed on the subject’s face during the two-plus decades since the portrait had been taken. I am likely to be only the second person to break the packet seals in some 140 years.

For an excellent description of the elements of a daguerreotype packet, visit the Library Company of Philadephia’s online exhibit, “Catching a Shadow: Daguerreotypes in Philadelphia 1839-1860.” Ω

“In this portrait we see a woman probably approaching forty yet still wearing the popular stiff, busked corset, and her dress is as tightly fitted over it as if she were a teenager.”

I am fortunate to have several daguerreotypes in my early image collection that were featured in one of the two seminal books on Victorian fashion by Joan Severa, former curator of costume at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. My Likeness Taken: Daguerreian Portraits in America, 1840-1860 was released in 2006, as the followup to 1995’s Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900. Both volumes were published by Kent State University Press.

In My Likeness Taken, Severna wrote of this image, “Few details testify so perfectly to the power of fashion influence as the persistent use of tight corseting. In this portrait we see a woman probably approaching forty yet still wearing the popular stiff, busked corset, and her dress is as tightly fitted over it as if she were a teenager. The corset makes for a rigid, upright posture.

“The sleeves are of the new, narrow shape, which became the preferred sleeve form by 1843. The collar is wide, in early forties style, and lappets have been laid under it and pinned with a brooch at the throat.

“The daycap is of the early forties shape, with a very deep brim that has been turned back so that its edge ruffle frames the face. The ribbon strings are tied closely under the chin and fall in lappets. Only in the later forties were the capstrings left open.

“The hair is done in short sausage curls at the crown, where it fits under the puffed back of the daycap.”

This image is also notable for its early date. The Daguerreotype process did not reach America until the end of the 1830s and was not viable for commercial use until exposure times could be cut down to a period that the sitters could bear.

“Americans began to experiment with the process almost immediately. Neck clamps limited the movement of subjects during a sitting. Mirrored systems to increase light and improved chemical techniques reduced exposure times to less than one minute. Although it is impossible to say who created the first daguerreotype portrait, all the claimants were Americans, and the daguerreotype acquired a particularly American identity. Even the leading daguerreotypists in London and Paris advertised ‘Pictures taken by the American process,’” notes the Cornell University website for the exhibition “Dawn’s Early Light: The First Fifty Years of American Photography.”

The solarization of the ribbons on the sitter’s daycap and collar is explained by M. Susan Barger and William Blaine White in The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science: “Blue usually occurs in daguerreotypes that have overexposed highlights. The frequent appearance in cheap daguerreotype portraits of blue shirtfronts on men gave these daguerreotypes the name ‘bluefronts.’”

I would postulate that given the 1842 date Severna assigned the image based on the sitter’s clothing, the photographer—who was plainly adept at posing and lighting his subject in an open and appealing manner—may not yet have mastered the technical processes of the art form. He may have been, in modern parlance, a “newbie.” Ω