To: Miss Anna M. Ramsey

Richborough P.D.

Bucks County

Pennsylvania

C/O Mr. Ed Ramsey

Please forward

High Point

April 27th ‘84

Dear Cousin Anna,

Yours of April 4 received. Was so glad to hear from you. I had looked for a letter for some time from Aunty. But have treasured up my last one from her. Anna, I sympathize deeply with your in your affliction. Your loss is her gain. But it is so hard to part with those we love so dearly but Aunty has only passed from this wicked world to a brighter and better one beyond. But oh the loneliness and sadness in the home without a mother or father. My heart aches for you, well I do remember the bitter pangs of suffering I passed through when I had to give up my dear mother. It seemed as though all the sunshine had gone out of the world. To this day I grieve for her. But time changes all things and we must be reconciled.

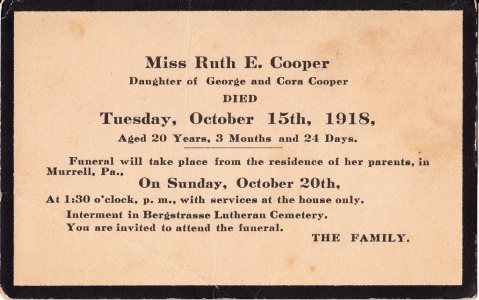

I was not surprised when we received the notice of Aunty’s death. From what you had written to me I was expecting it. But felt very sad indeed. I wanted to come east last fall to see you all once more but Jeff was sick so long and so bad that we could not leave him. I think from what you tell me about Aunty she must have been (in her sickness) very much like cos Kate Hume (McNair). She did not suffer pain but had that distress feeling and sick at her stomach. She had a cancerous tumor.