Ω

Ω

“The iron-gray hair was deep-dyed with of blood. Even the walls and low ceiling of the little living room bore evidence of the tragedy in dull garnet blotches.”

Continued from Part One.

On Saturday morning, 8 February, the temperatures were frigid. Henry Flook was up early, hauling wood. As he drove his team past Jane Bower’s cabin, Flook noted immediately that there was no smoke issuing from the chimney and no other sign of activity. By piecing together the newspaper accounts, it can be surmised that a concerned Flook returned at lunchtime with two other local men and found the cabin’s front door open a crack. After knocking and shouting raised no reply from within, the Sun reported that the trio entered and beheld “the ghastly sight of a human body cut into ragged pieces scattered on the floor before them.”

The newspapers went on to print every salacious detail of the murder scene found by Flook and his companions. For example, from the Sun, “The little living room was bespattered with blood and chunks of flesh and bone all scattered in a heart-sickening disorder. From beneath a portion of the woman’s torso, the bloody handle of an axe protruded…. Surrounded by blood-soaked garments lay parts of her dismembered body. In a corner, Flook found the woman’s head, the jagged flesh of the neck telling how the murderer hacked and hacked in his apparent insane desire to sever it from the body. The iron-gray hair was deep-dyed with of blood. Even the walls and low ceiling of the little living room bore evidence of the tragedy in dull garnet blotches. Bits of bone and tatters of flesh were stuck to the window panes …. The mass of flesh and bones, chopped into little bits the size of a marble, presented a sickening sight [that] declared the murderer must have hacked at the body fully two hours before completing his fiendish work.”

After making the terrible discovery, the frightened men went straight to the authorities. The resulting investigation found that “there was little, if any, struggle on behalf of the victim. In the death chamber, there was an overturned chair that seemed to have fallen with the woman when she was struck and killed. In a puddle of coagulated blood was a leather purse containing a little money, showing that robbery was not the motive,” noted the Sun. The beds in the cabin had not been slept in and a wound 24-hour clock was still working on Saturday afternoon—both indicating that the killing occurred late Friday afternoon or evening.

“State’s Attorney Worthington is investigating the death of Mrs. Sarah E. Weddle, widow, who died near Myersville April 14th. Certain discoveries have aroused the suspicion of the authorities.”

Dayton (Ohio) Herald, 25 February, 1903: “Mrs. Amy Snyder, 52, the wife of Aaron Snyder, an expressman, of 223 South Montgomery Street, was arrested Tuesday afternoon by Sergeant Fair and assistants, on suspicion of having performed a criminal operation on Miss May Smith, 19, of Xenia, which resulted in her death.”

Louisville (Kentucky) Courier-Journal, 26 March, 1903: “Miss Stella H. Stork, a pretty young woman whose home was at Huntingburg, Ind. … died at the private hospital of Dr. Sarah Murphy, 1018 West Chesnut Street, Tuesday afternoon. While peritonitis was the direct cause of death, this was brought on by a criminal operation….. George Lemp, a Southern Railway conductor, who came to Louisville with the girl last week, was arrested … but denied he had any knowledge of the girl’s condition.”

Scranton (Pennsylvania) Tribune, 27 March, 1903: “The sudden death of Mrs. Martha E. Rosengrant, widow of the late William Rosengrant, was the occasion of an inquest by Coroner Tibbins…. Mrs. Rosengrant was found dead in her bed at her home on Foundry Street on Wednesday morning…. The verdict of the jury was that Martha Rosengrant came to her death from a criminal operation performed upon her by someone to the jury unknown.”

Frederick (Maryland) News, 30 April, 1903: “The people of Myersville and vicinity are excited by the discovery of what appears to be evidence that the death of Mrs. Sarah E. Weddle, which occurred April 14, was due to a criminal operation. Mrs. Weddle was sick for about two weeks before her death.”

♦♦♦♦♦♦

When she died during the quickening Spring of 1903, widow Sarah Weddle left five young children as orphans. The lingering evidence shows she was one of the uncounted thousands of Victorian and Edwardian women who, when they fell pregnant, turned to “female pills”—herbal abortifacients advertised openly albeit with coded language—or to “criminal operations,” as illegal abortions were termed in the press.

Continue reading “Sarah Hoover Weddle: Lost to a “Criminal Operation””

New Year’s Eve was celebrated on 31 December for the first time in 45 B.C. when the Julian calendar came into effect.

Continue reading “New Year’s Eve: Roaring End, Rowdy Beginning”

“It was the purpose of the author to describe a number of novel and curious effects that can be obtained by the aid of the camera, together with some instructive and interesting photographic experiments.”—F. R. Fraprie, 1922

By Beverly Wilgus

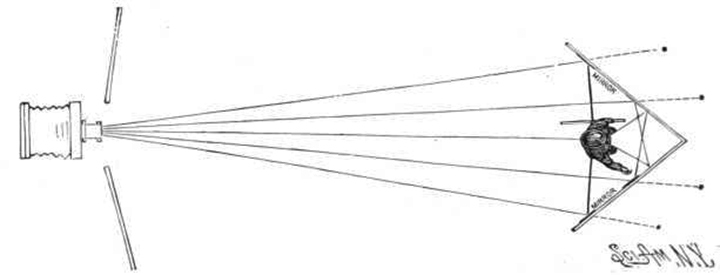

In 1893, H. P. Ranger was granted Patent No. 505,127 for a “Mirror For Use In Photography.” This was a device comprised of two adjustable mirrors set at an angle. When a subject was placed in front of it, his or her image was reflected in each mirror and that reflection was again reflected, resulting in five or more figures—the number of figures determined by the angle of the mirrors.

The above schema is from an article published in Scientific American in the 1890s that was included in the 1896 book Photographic Amusements by Frank R. Fraprie and Walter E. Woodbury. My husband and I own a copy of the 1931 edition that still contains the original illustrations.

Also from the book is the illustration above: “Diagram Showing The Method Of Production Of Five Views of One Subject By Multiphotography.”

Continue reading “Photo-Multigraphs: The Mirror and the Camera”

“What makes photography a strange invention is that its primary raw materials are light and time.”—John Berger

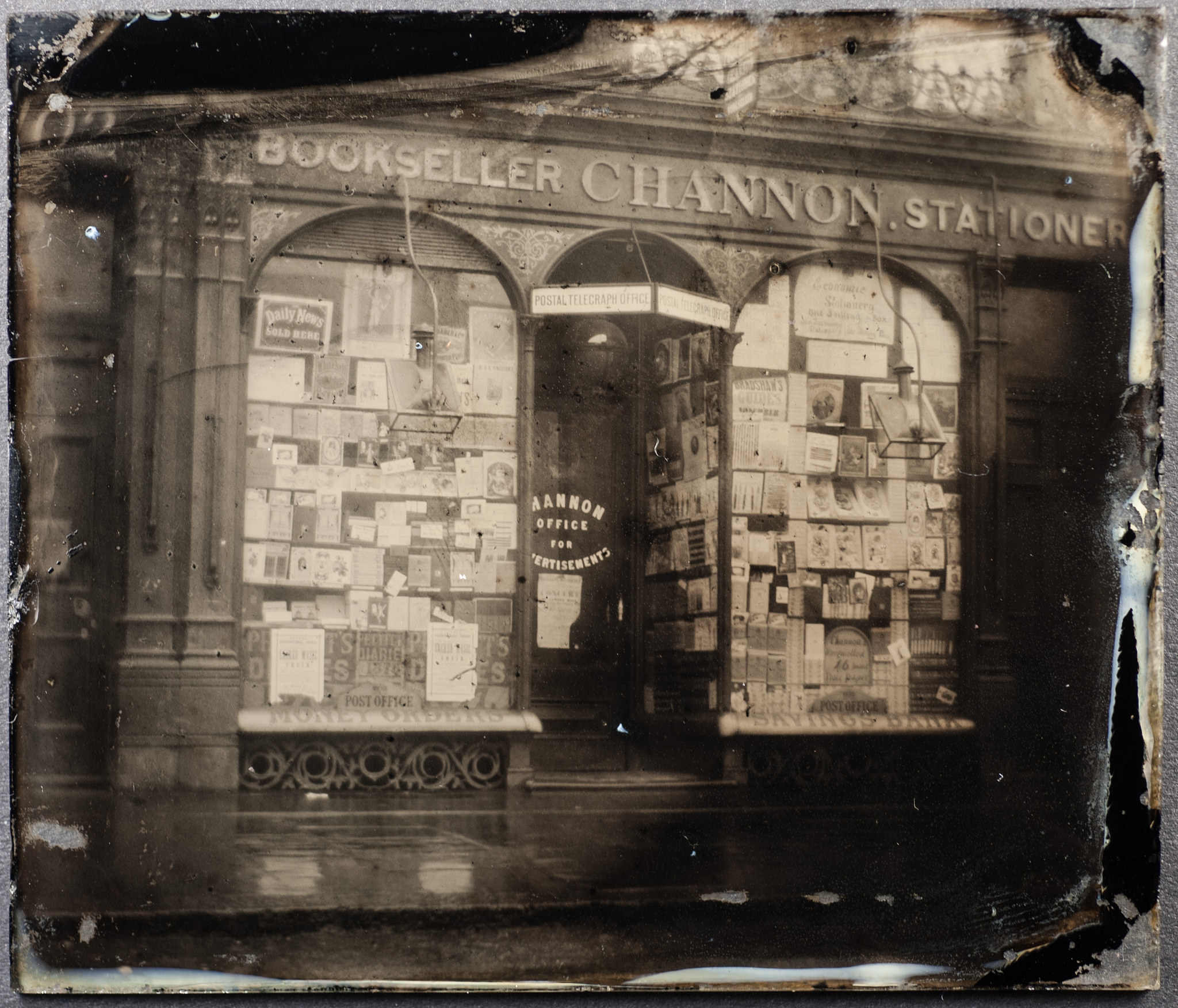

James Morley writes of this ambrotype of Channon Post Office & Stationers, Brompton Road, London, circa 1877: “I have found historical records including newspapers, electoral rolls, and street directories that give Thomas Samuel Channon at a few addresses around Brompton Road, most notably 96 and 100 Brompton Road. These date from 1855 until early into the 20th century. These addresses would appear to have been immediately opposite Harrods department store.”

The limited research I have done on this image, which is a stereoview card marked “State Block, New Hampshire, W.G.C. Kimball, Photographer,” leads me to believe it shows mourners of Concord, New Hampshire native Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804–October 8, 1869), 14th President of the United States (1853–1857).

The banners affixed to the carriage read “We miss him most who knew him best” and “We mourn his loss,” as well as another phrase that ends in the word “forget.” The image also features an upside-down American flag with thirteen stars.

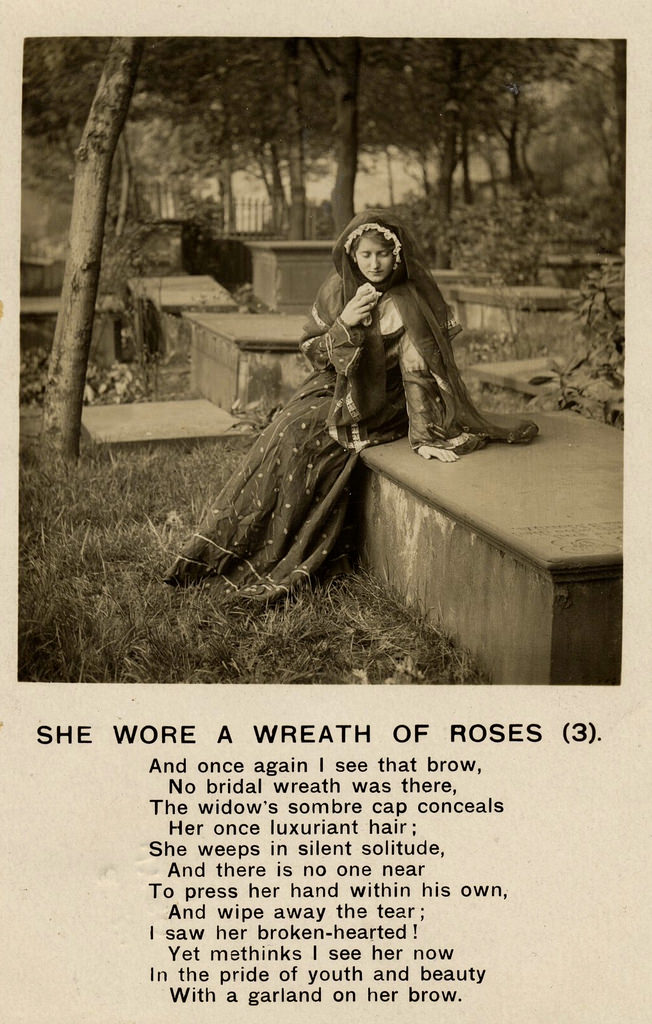

Faux widow + faux husband’s tomb + mourning doggerel = Happy birthday?

This Edwardian postcard from my collection shows a woman in the fullness of her beauty sat atop a chest tomb that is arguably from much earlier in the Victorian era. Whilst the woman is not dressed in conventional mourning, she does wear a recognizable widow’s bonnet—a necessary prop for the maudlin poem below the image: “She wore a wreath of roses, And once again I see that brow, No bridal wreath was there, The widow’s sombre cap conceals Her once luxuriant hair; She weeps in silent solitude, And there is no one near To press her hand within his own, And wipe away the tear; I saw her broken-hearted! Yet methinks I see her now In the pride of youth and beauty with a garland on her brow.”

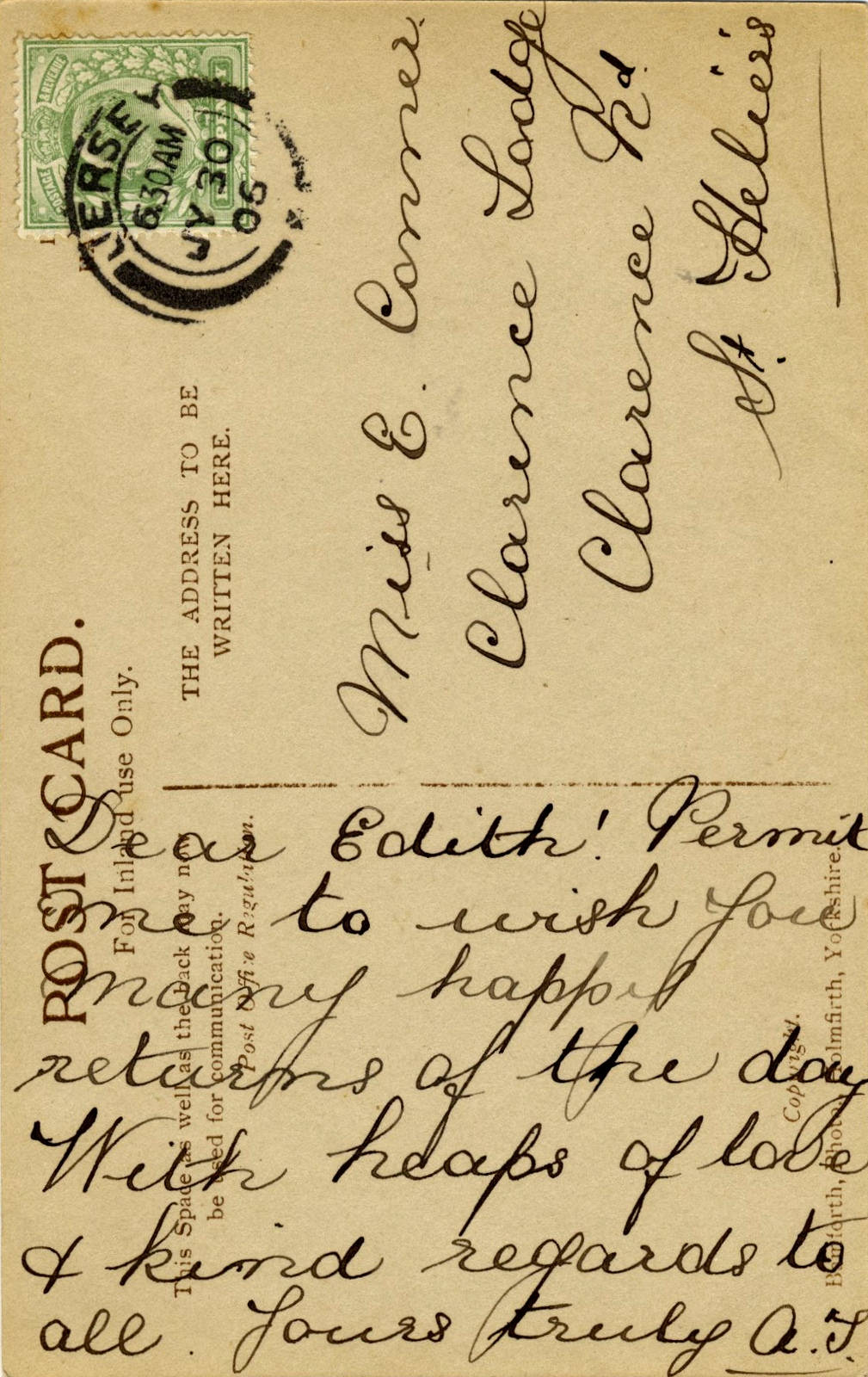

The postcard was mailed from somewhere on the Channel Island of Jersey, off the coast of Normandy, France, at 6:30 a.m., 30 July, 1905, to Miss Edith Conner at Clarence Lodge, Clarence Road, in the Jersey town of St. Helier.

The sender’s message was both cheerful and bizarrely inappropriate, as it appears to recognize the recipient’s birthday: “Dear Edith! Permit me to wish you many happy returns of the day. With heaps of love & kind regards to all. Yours truly, A.J.”

One must wonder if the little shop on the High Street was dreadfully low on carte postals. Ω

“Thank you dear for the nice letter you sent us and all the kisses. Hope you are a good boy. Did you throw Herbert out of bed Sunday morning?”

Today’s postcards convey “Wish you were here!” almost exclusively, but in the first decades of the 20th Century this method regularly moved information to friends and family who resided even just a few miles away. The short messages often read much like modern email, and when in combination with the photos on the front, can seem like old-school versions of modern Facebook posts.

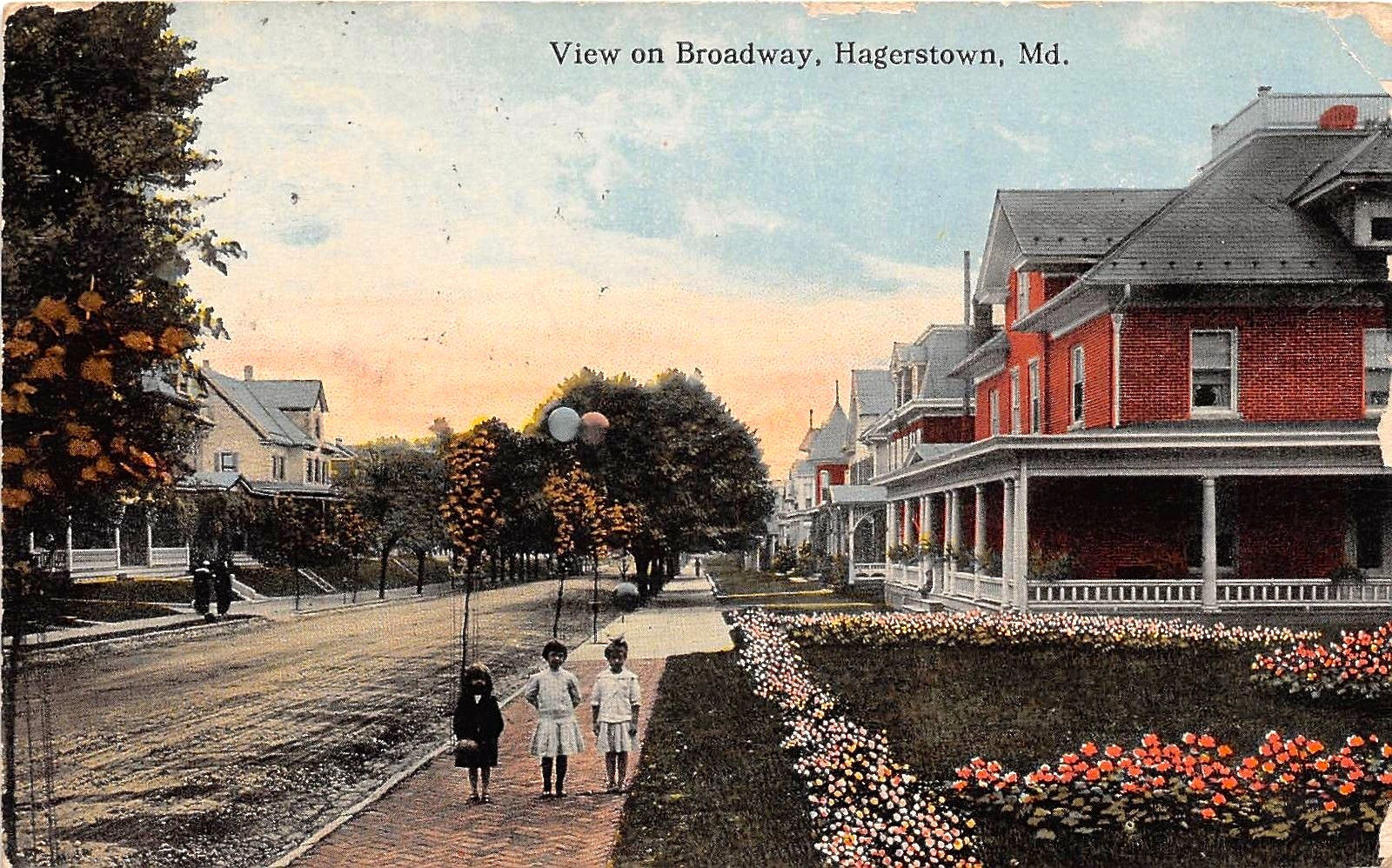

On 4 March, 1914, this cheerful, beautifully colored postcard of Hagerstown, Maryland’s Broadway (above) was sent to Mrs. C. L. Pennison, Newton, Massachusetts, care of Peckitts on Sugar Hill. The message reads, “Dear Catherine, I was pleased to get your card on Monday while at home. But surprised to hear you are in the White Mountains. I hope you will soon recover your health up there. We were in the midst of a blizzard Monday but are enjoying pleasant weather now. I am well and enjoy my work. Yours, B.”

This postcard of the Washington Street Bridge, Monticello, Indiana, was addressed to Miss Ruthie Brown of Modesto, Illinois, and mailed 4 July, 1913. The reverse reads, “Dear Ruth: This is where I am spending the day. This morning our car struck a buggy just as we were going up the hill beyond this bridge. I hope you are having a lovely vacation. Would like to hear from you very much. Grace Mc. 1 Danville, Ind.”

Beverly Wilgus, the owner of this example, writes, “This postcard was mailed by a grandfather to his granddaughter in November, 1912. The caption ‘Tommy’s first and Turkey’s last picture” [has an] unpleasant edge. The image is embossed and gives the figures a slight 3D effect. It was sent to Dorothy Flower in North Uxbridge, Massachusetts, by Grandpa Midley.”

The message reads, “Dear Dorothy: How would you like to have your picture taken this way? I suppose you would rather have some of the turkey to eat. Hope you will have some for your Thanksgiving dinner. Am going to try to get to No. Uxbridge to see you soon.”

Margaret Ripley was a nurse in France during World War I. The above is one of a series of postcards she sent to her sister back in Surrey, England. “Had 2 nice days here unfortunately Louvre & all museums shut but seen as much as possible. Off to Dunkirk tomorrow to typhoid hospital—so glad to feel we may at last get real work in connection with war. Have enjoyed our week’s holiday very much & were hoping to stay on here a few more days. Love to E & children. Hope they are well again. Mar.”

Although the photographic image is from a decade previous, this postcard’s stamp was cancelled 24 December, 1922. Addressed to Mr. S. Schmall, 4549 Calumet St., Chicago, Illinois, the delightful message reads: “Thank you dear for the nice letter you sent us and all the kisses. Hope you are a good boy. Did you throw Herbert out of bed Sunday morning? Love to you & all. Aunt Alice.”

Postmarked 30 October, 1917, this postcard was sent by the United Brethren Sunday School of Myersville, Maryland, to Helen Keller and family. “U B ready for the U.B. Rally. We need you on Rally Day. Remember the date: Nov. 11th. Do not disappoint us. Help us make this our best Rally Day.” (If there was a smiling emoticon after “Do not disappoint us,” I would feel less creeped out.)

According to Holidays, Festivals, and Celebrations of the World Dictionary, “In liturgical Protestant churches, Rally Day marks the beginning of the church calendar year. It typically occurs at the end of September or the beginning of October. Although not all Protestant churches observe this day, the customs associated with it include giving Bibles to children, promoting children from one Sunday school grade to the next, welcoming new members into the church, and making a formal presentation of church goals for the coming year.”

Beverly Wilgus writes, “This multiple-print, real photo postcard shows two soldiers in a studio prop biplane flying over a real San Antonio streetscape. A banner reading ‘San Antonio 1911’ flies from the wing. Even though the plane is obviously phony, the two airmen appear to be real pilots since the message on the back reads, ‘Our first lesson what do you think of it? Geo.’”

I’m thinking Photoshop, version 1.911. Ω

“Oh! I do like to be beside the seaside! I do like to be beside the sea! I do like to stroll along the Prom, Prom, Prom! Where the brass bands plays tiddely-pom-pom-pom! So just let me be beside the seaside! I’ll be beside myself with glee and there’s lots of girls beside, I should like to be beside, beside the seaside, beside the sea!”

This British ambrotype shows either a mother (right) with three daughters, or four sisters of disparate ages, posed on the exposed ground of a tidal estuary or river. Their fashions date to about 1870. The littlest girl is either carrying her bonnet or a bucket. Ann Longmore-Etheridge Collection.

Capocci & Sons, ice cream vendor, on the beach during a sunny, happy day at Bournemouth, Dorset, in the 1890s. The 1891 census enumerated Celestine Capocci, a 51-year-old ice cream maker born in Italy, and her large family living at 5 St. Michael’s Cottages, Holdenhurst, Bournemouth. Glass-plate negative courtesy James Morley (@photosofthepast). The identification of the ice cream vendor was made by EastMarple1, who is a collector and historian at Flickr.

Three elegant young adults on the deck of a ship or a seaside pier, circa 1900. Glass-Plate negative from the collection of James Morley.

On the beach at Trouville, Normandy, France, in September 1926. Paper print from the collection of James Morley.

Although posed in front of a backdrop, this girl was genuinely at the seaside, as Littlehampton, West Sussex, remains a vibrant holiday community to this day. Whilst photographers roamed the beach at Littlehampton and other resort towns, photography studios with their painted seaside scenes provided a second souvenir option. This Carte de Visite, taken circa 1900, is courtesy Caroline Leech.

“The most easily identified and most commonly found British tintype are the seaside portraits where families pose with buckets and spades in the sand or lounge in deck chairs on pebbled beaches with wrought iron piers in the background,” writes the administrator of the site British Tintypes. “The seaside might also be the one place where middle class people could safely and easily have a tintype made—as a fun, spur-of-the-moment amusement in keeping with other beach entertainment.” Tintype, mid-1890s, Ann Longmore-Etheridge Collection.

Ω

Lyrics to “I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside,” written in 1907 by John A. Glover-Kind.

“I’ve felt for the first time in my life the joyful consciousness that I am truly loved by a truly good man, one that with all my heart I can love and honor… one who loves me for myself alone, and with an unselfish, patient, gentle affection such as I never thought to waken in a human heart… a man in whom I can trust without fear, in whose principles I have perfect faith, in whose large, warm, loving heart my own restless soul can find repose.”—Anna Alcott Pratt, 1859

“[M]y love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me to you with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break… ”—Sullivan Ballou, letter to wife Sarah, 14 July, 1861.

“To lovers, I devise their imaginary world, with whatever they may need, as the stars of the sky, the red, red roses by the wall, the snow of the hawthorn, the sweet strains of music, and aught else they may desire to figure to each other the lastingness and beauty of their love.”—Williston Fish, A Last Will, 1898

Ω

I am delighted to announce that I have joined the staff writing team at Historical Diaries. Material from Your Dying Charlotte will appear there regularly.

I am also delighted to note that I will be able to bring you material from James Morley, who maintains his vast and wonderful collection on flickr, here, and is the founder of the blog What’s That Picture? His twitter handle is @PhotosOfThePast.