“When old Francis died in 1913, Dad sent him off in a hearse pulled by four black horses followed by mutes carrying ostrich feather wands and a procession of friends and family in the deepest mourning possible.”—Barbara Nadel

New Year’s Eve was celebrated on 31 December for the first time in 45 B.C. when the Julian calendar came into effect.

Continue reading “New Year’s Eve: Roaring End, Rowdy Beginning”

In about 1849, a mother and child were photographed in a New York town where visionaries struggled to change the world.

A long inscription is penciled inside the case of this daguerreotype: “The picture of Flora and her mother, taken when she was three years old at McGrawville, Cortland Co., NY.

“I’ll think of thee at eventide/ When shines the star of love/ When Earth is garnished like a bride/ and all is joy a-bove/ and when the moon’s pale genial face/ is shed or [sic] land & sea/ and throughs [sic] around her soft light/ t’is then I think of thee. EM

“Flora & I are in the parlor as I write this, talking of the war, etc. etc. Henry …?… is buried Thursday Oct. 30th, ’62.”

The sentimental verse is likely based on “Better Moments,” by poet Nathaniel Parker Willis (1806-1867), printed in 7 July, 1827’s New-York Mirror and Ladies Literary Gazette, Volume IV, as well as and in the New Mirror’s Poems of Passion in 1843. Willis’s poem includes the lines: “I have been out at eventide/ Beneath a moonlit sky of spring/ When Earth was garnished like a bride/ And night had on her silver wing.” It is uncertain whether variants of Willis’s poem existed that included the stanza scriven in the case, or whether the writer “borrowed” a few lines of it for his or her own poetic creation.

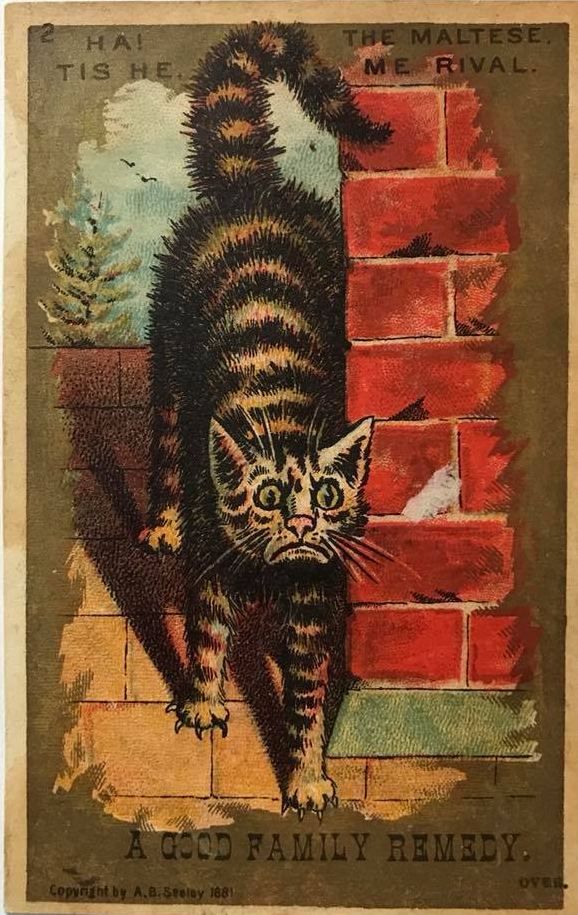

Long before Internet memes, the obsession with yowling, murderous, disdainful, aloof, and weirdly adorable felines produced trade cards that are still collected today.

“Connecticut River at Hartford 18 feet above low water mark. Heavy rain still prevailed, with much thunder.”—Beckwith’s Almanac

Harriet Leonard Hale, scion of an old and venerable New England family, was the third child and only daughter of Russell Hale. Hale was born 22 July, 1799, in Glastonbury, Hartford County, Connecticut, and died 13 April, 1849, in that same place. Harriet’s mother, Harriet Ely, was born 17 April, 1803, in Agawam, Massachusetts, and died 2 September, 1880. Russell was the son of Thomas Hale of Glastonbury (10 June, 1768–12 Feb., 1819) and Lucretia House (1771–24 September, 1835). The Hales descended from Samuel Hale, born 1 July, 1615, at Watton-at-Stone, Hertfordshire, England, who came to Connecticut as a young man, married Mary Smith in about 1642, and died in Glastonbury on 9 November, 1693.

Harriet Hale was born 14 April, 1833, in Glastonbury. Her two older brothers were Robert Ely (1827–1847) and Henry Russell (1830–1876). The 1850 Census of Glastonbury included Harriet Ely Hale as a widow, together with her daughter Harriet and her son Henry, a farmer. It is the only census that Harriet Hale Fox appeared on, as the one compiled a decade previously, when she was seven in 1840, listed the names of household heads only.

At age 18, Harriet wed blond, bearded, and bespectacled Henry Fox, a man twelve years her senior, on 5 October, 1851. He had been born in East Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut, 19 April, 1821, and was the son of Leonard Fox (1792–1866) and Hannah Nicholson (1795–1894). The Fox family had been in New England since emigrating from London in the 17th century. Members of the clan participated in the Revolutionary War, and Leonard Fox fought in the War of 1812.

Continue reading “Harriet Fox: Drowned at the Wethersfield Ferry”

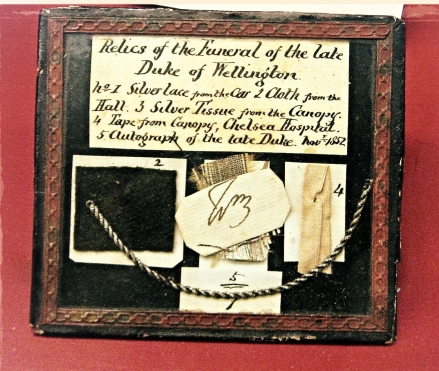

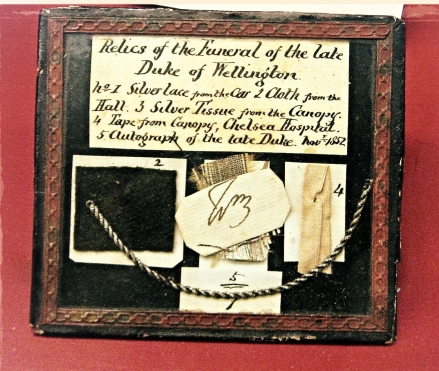

In Britain in the 1800s, the widow’s grief of Queen Victoria helped spur the creation of mourning jewelry, but in the 1600s, the impetus was the judicial murder of an anointed king.

Charles Stuart, later King Charles I, was born in Fife, Scotland, 19 November, 1600, to King James VI of Scotland, later James I of a unified Britain, and his wife Queen Anne of Denmark. He was a second son, never meant to rule. Yet, Charles had the role of heir foisted on him at the death of his beloved, handsome, and accomplished older brother, Henry, Prince of Wales, who died unexpectedly in 1612.

Charles was small, sickly, and had a stammer. He was also intellectual, loved and patronized the arts, favored elaborate high Anglican worship in the age of the Puritans, and married a Roman Catholic—the delicate and beautiful Princess Henrietta Maria of France, known as Queen Mary, after whom the U.S. state of Maryland is named. Charles also believed profoundly in the Divine Right of Kings, was willful and stubborn, and refused to make the compromises that could have prevented a civil war, the destruction of the monarchy, and his own death.

As had the life his similarly-natured paternal grandmother, Mary, Queen of Scots, his own earthly days ended in execution by beheading on 30 January, 1649. His final words were “I go from a corruptible to an uncorruptible crown, where no disturbance can be.”

Continue reading “His Good Late Majesty: Memorial Jewelry for King Charles I”

All of this historic context, moreover the genetic material of their ancestress, was not valued by her descendants, who found her mourning brooch too disgusting to keep.

In about 1996, while trawling for hair-work brooches on eBay with a tax return smoldering in my pocket, I found a listing with a ridiculously blurry photo of what looked like—just maybe—a Regency-Era mourning brooch. The accompanying item description encapsulated the prevailing 20th-Century attitude toward mourning jewelry. As I recall, it read something very close to “We found this pin that belonged to grandma. It has hair in it! Eww! Get it out of our house!” I obliged for about $40; no other bidders were willing to take the chance with that kind of sales photo. One- by three-quarters-inch in size, this type of small brooch was known as a “lace pin” and used to secure veils, ribbons, pelerines, and other accessories. They were also worn by men as lapel pins.

The 210-hundred-year-old gem that I received was made of 10-karat or higher plain and rose gold with completely intact niello and inset faceted jet cabochons. (Niello is a black metallic alloy of sulfur, copper, silver, and usually lead, used as an inlay on engraved metal.) The brooch was in pristine condition, bearing the inscription “Mary Palmer. Ob. 3 July 1806, aet. 38.” The abbreviation “Ob.” is from the Latin obitus—“a departure,” which has long been a euphemism for death. “Aet.” is from the Latin aetatis—“of age.”

Victoria’s grief drove into high gear the already strong public market for jewelry to be at worn during all stages of mourning.

At the close of the 18th century and the early years of the 19th, memorial pieces with hair were generally small, delicate, and graceful. However, the oncoming Victorian era would turn “the entire ritual of mourning into a public display, and the jewelry changed accordingly, becoming larger, heavier, and more obvious,” wrote the curators of the Springfield, Illinois-based Museum of Funeral Customs in Bejeweled Bereavement: Mourning Jewelry—1765-1920.

In December 1861, Queen Victoria’s beloved consort, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, died of what is thought to have been typhoid fever. Married for twenty-one years, their happy union resulted in the birth of nine children. The forty-two-year-old prince’s demise shattered Victoria. For the rest of her life, the queen wore mourning and required many courtiers who served her and who attended court functions to do the same.

Victoria’s grief drove into high gear the already strong public market for jewelry to be worn during all stages of mourning. For example, in the first nine months, the only acceptable jewelry was made of black glass, dyed pressed animal horn, gutta-percha (a latex plastic derived from tropical evergreens), vulcanite and ebonite (rubber treated with sulfur and heat), bog oak (fossilized peat), or carved from jet (a fossilized wood that washes up on west coast Yorkshire beaches, and was extracted from shale seams, particularly around between Robin Hood’s Bay and Boulby). In later stages of mourning, gold or pinchbeck (a composite metal) and hair-work jewelry commemorating the deceased was worn. Many of these items bore the motto “In Memory Of” and featured heavy black enameling.

The historical importance of March 1843 daguerreotype was forgotten until now.

A new image of John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth president, will be presented for sale by the auction house Sotheby’s later this year. The March 1843 daguerreotype, which Quincy Adams gifted to a friend, remained in the recipient’s family through the generations although its historical importance was forgotten. The image was made during a sitting with early photographers Southworth & Hawes that yielded at least two daguerreotypes. A copy of the other now resides in the collection of the New York Metropolitan Museum.

There is a third, badly damaged daguerreotype of Quincy Adams held by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. Adams disliked it, noting in his diary that he thought it “hideous” because it was “too close to the original.” More than a hundred years later, in 1970, the daguerreotype was bought for 50 cents in an antique shop. After identification, it was eventually donated it to the nation.

Continue reading “Sit Down, John: An Adams Image Rediscovered”

“Being a Grave Gardeners lets them contribute to a place that holds both personal and historic resonance.”

Through the stone gates of Woodlands Cemetery, a tranquil, verdant oasis thrives in the heart of University City. The Victorian necropolis, the last undeveloped parcel of the estate of botanist and plant collector William Hamilton, was preserved and a repurposed as a rural cemetery in 1840 as the city and University of Pennsylvania pushed westward. Today, The Woodlands is flourishing with the aid of creative placemaking and inventive programming.

The Grave Gardeners program is the most recent brainchild of Woodlands’ executive director Jessica Baumert and her staff. The cemetery is home to hundreds of “cradle graves,” tombs with both headstones and footstones connected by two low walls that create a bathtub-like basin. In the 1800s, family members of the deceased filled the French-style “cradles” with living, blooming coverlets of flowers. Cultivating these gardens on weekend outings to sylvan cemetery grounds like The Woodlands was a way of keeping a loved one’s memory alive. As descendants scattered and their memories of connections to Victorian ancestors faded, the gardens died out. The Woodlands’ Adopt-a-Grave program enlists the help of volunteers to revive these now scruffy patches of dirt and grass, one grave at a time.

To read this wonderful article in its entirety, click the link below.

Source: Gardeners Bring Cradle Graves Back From The Dead | Hidden City Philadelphia

Thank you to my dear cousin, Elizabeth Harrison, for calling this to my attention.