Ω

A selection of unidentified daguerreotype and ambrotype portraits.

Ω

Although there had been settlers in the area since the 1830s, the Lillibridges were part of an immense rush of newcomers to the Iowa territory during the 1850s.

Today, the prairies of Iowa are all but gone—their restoration the scheme of environmentalists and concerned volunteers. But when these great grass seas last existed, it was the grandparents of the baby above, Clair Miles Lillibridge, who arrived to radically reshape them.

Clair’s father Leverett Lillibridge, born 25 June, 1851, was the son of John Lillibridge (b. 1816) and Mary Rexford (b. 1815), who married in Lebanon, Madison County, New York, 25 May, 1836, and had seven children, of which Leverett was the fourth. The family went west to what became the town of Manchester, Delaware County, Iowa, almost a decade before Leverett’s birth in 1851. The namesake of John and Mary’s son was his maternal grandfather, early settler Leverett Rexford, who in 1841, according to The History of Delware County, Iowa and Its People, “built a log cabin near the Bailey home, which was later inhabited by John Lillibridge.”

Although there had been settlers in the area since the 1830s, the Lillibridges were part of an immense rush of newcomers to the territory during the 1850s. “Families camped at the Mississippi, waiting their turn for ferryboats to the other side. In only a few years these settlers would turn the forests and prairies into plowed fields,” notes Iowa Public Television. “Farmers arriving from the many different regions of the United States brought their special agriculture with them. Those from New England and New York carried the seeds for plum, apple and pear trees. Kentuckians brought their knowledge of improved seed and livestock breeding. From Pennsylvania and Ohio fine flocks of sheep came to graze in the dry pastures of southern Iowa.”

One harrowing story of the early years of Manchester took place when Leverett Lillibridge was two. “Jane and Eliza Scott, whose home was near Delhi…in the spring of 1853, attempted to ford Spring Branch, a mile above Bailey’s, but the water was so high that their horse and wagon were swept [away] and the horse was drowned. The current carried one of the girls safely to shore, but the other was drawn into the eddy but was finally rescued by her sister, who succeeded in reaching her with a pole and drawing her to shore. One of the girls reached Bailey’s cabin, but was so exhausted she could not for some time explain the situation. As soon as she made herself understood, Mrs. Bailey left her and hastened to the locality where the other girl was expected to be found. On her way she met John Lillibridge and they together carried the insensible girl from where they found her to Mr. Lillibridge’s horse and placing the limp body on the animal’s back, she was conveyed to the Bailey home, where both the unfortunate girls were given every attention.”

Continue reading “The Lillibridges: From Prairie Grass to Cream”

An amazing story about abolition-era rock stars.

Tom Maxwell | Longreads | March 2017 | 9 minutes (2,170 words)

On March 18, 1845, the Hutchinson Family Singers were huddled in a Manhattan boarding house, afraid for their lives. As 19th Century rock stars, they didn’t fear the next night’s sellout crowd, but rather the threat of a mob. For the first time, the group had decided to include their most fierce anti-slavery song into a public program, and the response was swift. Local Democratic and Whig papers issued dire warnings and suggested possible violence. It was rumored that dozens of demonstrators had bought tickets and were coming armed with “brickbats and other missiles.”

“Even our most warm and enthusiastic friends among the abolitionists took alarm,” remembered Abby Hutchinson, and “begged that we might omit the song, as they did not wish to see us get killed.”

It wasn’t that most people didn’t know the Hutchinsons were…

View original post 1,915 more words

“In terms of symbolism, the loss of the soul is the same as that of the body, representing a crossing over to a place that we do not know or understand.”

This unusual mourning brooch, which dates to between 1830 and 1840, is a late example of the sepia painting technique popular up to a century earlier. Sepia miniatures in the neoclassical style, such as the one below right, were painted with dissolved human hair on ivory tablets and typically feature weeping women and willows, funeral urns, graves, and other scenes and symbols of loss.

This brooch is dedicated by reverse inscription to “M. Thayer,” but little more can be known about the deceased, as the inscription includes no dates of birth or death. Thayer was likely occupationally connected to the sea, although the image may be wholly allegorical. A ship sailing toward a distant safe haven, accompanied or guided by birds, may be read as the soul journeying toward the afterlife in the company of angelic beings.

“What makes photography a strange invention is that its primary raw materials are light and time.”—John Berger

James Morley writes of this ambrotype of Channon Post Office & Stationers, Brompton Road, London, circa 1877: “I have found historical records including newspapers, electoral rolls, and street directories that give Thomas Samuel Channon at a few addresses around Brompton Road, most notably 96 and 100 Brompton Road. These date from 1855 until early into the 20th century. These addresses would appear to have been immediately opposite Harrods department store.”

The limited research I have done on this image, which is a stereoview card marked “State Block, New Hampshire, W.G.C. Kimball, Photographer,” leads me to believe it shows mourners of Concord, New Hampshire native Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804–October 8, 1869), 14th President of the United States (1853–1857).

The banners affixed to the carriage read “We miss him most who knew him best” and “We mourn his loss,” as well as another phrase that ends in the word “forget.” The image also features an upside-down American flag with thirteen stars.

“Poor boy! I never knew you, yet I think I could not refuse this moment to die for you, if that would save you.”―Walt Whitman

The carte de visite (CDV) shows the young and almost impossibly handsome John Van Der Ipe Quick, born 27 August, 1829, in Lodi, Seneca County, New York, northwest of Ithaca. The CDV is a copy of an daguerreotype that was taken in about 1850, probably when he reached the age of 18.

John’s parents were farmer and Reformed Dutch Church member Christopher Quick and his wife Ellen Van Der Ipe, who was the daughter of John Van Der Ipe and Harriet Ten Eyck. Christopher Quick was born in South Branch, Somerset County, New Jersey, 14 August, 1798, to Abraham Quick (1766-1819) and Catherine Christopher Beekman (1766-1848). Abraham Quick, was, in turn, the son of farmer and Revolutionary War soldier Joachim Quick (1734-1816), who had been born in Harlingen, Somerset County, New Jersey, 22 July, 1734. His tombstone can be found in Harlingen Reformed Church Cemetery, Belle Mead, New Jersey. His wife, John’s great-grandmother, was Catherine Snedeker (1739-1815).

John’s father Christopher’s union with Ellen Van Der Ipe, who was born 3 November, 1798, in Neshanic, Somerset County, resulted in three daughters: Harriet Ten Eyck Quick, born 30 November, 1822; Maria (b. 1825, died young); and Catherine (b. 1827). After John arrived two more sons followed: Abram, born in 1832, and James, born in 1838. But the Quicks soon may have felt this verse from Job spoke to them most particularly: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb; naked I will return there. The Lord has given; the Lord has taken; bless the Lord’s name.”

The 1840s began pleasantly. Eldest daughter Harriet married Cornelius Peterson (b. 1823) on 8 December, 1841. Tragedy struck hard, however, when paterfamilias Christopher Quick died at age 44 on 9 January, 1842. At that time, the recorder of deaths at the Farmville Reformed Dutch Church had the habit of noting a biblical verse by the name of each entry; for Christopher Quick, he chose Mathew 6:10, “Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven.”

Christopher was buried in Lake View Cemetery, Interlaken, Seneca County, New York. In his Will, he bequeathed each of his children $100. His wife was left in charge of his property until his youngest child turned 21, then his estate was to be evenly divided between the children with one-third for his widow.

Harriet became pregnant at about the time of her father’s death, and her first child, a son named Christopher Quick Peterson in honor of his grandfather, was born 8 November, 1842. A life was taken and a new life given, but the cycle was far from finished: The youngest Quick, James, died 29 November, 1843, aged four years, eight months, and 15 days. (The registrar of deaths chose Isaiah 3:10: “Say ye to the righteous, that it shall be well with him: for they shall eat the fruit of their doings.”) The following year, John’s sister Harriet bore another son, Peter. In 1848, there was the birth of a third son, John Bergen Peterson, as well as the death of John’s little brother, Abram Quick, on 18 April, aged 16.

The 1850 Census enumerated the surviving Quick family in Lodi, with mother Ellen Quick running the family farm valued at $5,500. John was a laborer there, along with 14-year-old William Peterson, who may have been brother-in-law Cornelius’s younger brother. There was one more birth—that of Harriet’s son Abram, on 16 April, followed in short order by the death of John’s sister Catherine Quick on 1 October. A final Peterson child—this time a daughter named Mary, was born 1 November, 1856. (Happily, all of the Peterson children thrived and lived into the 20th century.)

A decade later, on the 1860 Census of Covert—a Seneca County town not far from Lodi—Ellen, John, and William Peterson lived with Hannibal and Maria Osborn and their children—the Quick family farm presumably sold. Osborn was a sawyer—a man who sawed wood, particularly using a pit saw, or who operated a sawmill. John and William were listed as sawyers as well, and this may have been where John’s career rested had the Civil War not removed him from his native state.

John joined the Union Army on 6 August, 1862, at age 29, for a three-year term, entering as a private in the 126th New York Infantry, according Civil War muster roll abstracts. In his enlistment records, John was described as having blue eyes, brown hair, a fair complexion, and standing 5’8″.

By September 1862, John was in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). On 12 September, the troops of Confederate Major General Stonewall Jackson attacked and captured the Union garrison stationed there. The muster rolls state that John surrendered to the enemy on 15 September and was paroled 16 September. The Union Army: a History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861-65, explains, “The men were immediately paroled and spent two months in camp at Chicago, Ill., awaiting notice of its exchange. As soon as notice of its exchange was received in December, it returned to Virginia, encamping during the winter at Union Mills.”

The muster rolls note that John was present during the entirety of 1863, which means that he fought at Gettysburg. According to the regimental history, “In June, 1863, [the 126th] joined the Army of the Potomac, and was placed in Willard’s Brigade, Alex. Hays’ (3d) division, 2nd corps, with which it marched to Gettysburg, where the regiment won honorable distinction, capturing 5 stands of colors in that battle. Col. Willard, the brigade commander, being killed there, Col. Sherrill succeeded him, only to meet the same fate, while in the regiment the casualties amounted to 40 killed, 181 wounded and 10 missing.”

A monument to the 126th can be seen at Gettysburg today. In part, it reads: “The regiment was in position two hundred yards at the left, July 2 until 7 p.m., when the brigade was conducted thirteen hundred yards farther to the left and the regiment with the 111th N.Y. and 125th N.Y., charged the enemy in the swale, near the source of Plum Run, driving them there from and advancing one hundred and seventy-five yards beyond, towards the Emmitsburg Road, to a position indicated by a monument on Sickles Avenue. At dark the regiment returned to near its former position. In the afternoon of July 3rd it took this position and assisted in repulsing the charge of the enemy, capturing three stands of colors and many prisoners.”

From 5 to 24 July, the 126th pursued Gen. Robert E. Lee to Manassas Gap, Virginia. By October, it was fighting in the Bristoe Campaign, followed by the battles of Brandy Station and Mile Run.

The muster rolls state that John Quick was on furlough from 6 to 16 February, 1864, presumably visiting his family in Seneca County. Once he had returned, he was promoted to corporal. His regiment had been hard hit by losses and seasoned men were being elevated to replace the dead. Returns from Fort Wood, Bedloe’s Island, New York City Harbor (where later the Statue of Liberty would be built), place John there in April 1864, where he was amongst the “enlisted men casually at post” on the 25th of that month.

Between 5 and 7 May, John fought in the Battle of the Wilderness, where the regiment lost five men, 62 were wounded, and 9 went missing. Just a few days later, he was at Spotsylvania Court House, where six died, 37 were wounded, and seven went missing.

The 126th saw further action at Totopotomy, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Weldon Railroad, the Siege of Petersburg, and Deep Bottom. But it was at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, where John’s luck ran out. According to the website for the battlefield’s preservation, “On August 24, Union II Corps moved south along the Weldon Railroad, tearing up track, preceded by Gregg’s cavalry division. On August 25, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth attacked and overran the faulty Union position at Ream’s Station, capturing 9 guns, 12 colors, and many prisoners. The old II Corps was shattered. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock withdrew to the main Union line near the Jerusalem Plank Road, bemoaning the declining combat effectiveness of his troops.”

It appears that amongst the many prisoners taken was Corporal John Quick. The muster rolls called him “missing in action at Ream’s Station since Aug. 25 ’64.” Another notation stated, “Captured Aug. 25.” It is believed that more than 2,000 Union soldiers were taken prisoner that day. However, in the correspondence of the Ontario County Times dated three days after his supposed capture, Quick was seemingly still with his unit:

“Casualties of the 126th Regt. N. Y. S. V.

Headquarters 126th N. Y. Vols.,

Camp near Petersburg, Va. Aug. 28, 1864.

To the Times:—The following is a list of the casualties of the 126th in the [battle] of Ream’s Station, Aug. 26th:

Killed—George M. Fuller, Co. D.

Wounded—Corp’l John Quick, Co. C, face; Aaron H. Abeel, Co. E, leg; Chas. Wolverton, Co. E, neck; 1st Sergt. Cornelius Alliger, Co. I, leg.

Missing and supposed to be prisoners: Sergt. Martin McCormick, Co. B; Isaac Miller, Co. C; Alex. Wykoff, Co. C; Michael Cunningham, Co. D; Chester B. Smith, Co. E; Andrew J. Ralph, Co. G; Edgar T. Havens, Co. G; Nathan D. Beedon, Co. B; Charles H. Dunning, Co. B; Frank Dunnigan, Co. G.

None of the wounds are necessarily fatal. I have prepared this list hastily.

Yours truly,

J. H. Wilder, Capt. Comd. Regt.”

The extent of John’s face wound, and how, when, and for how long he remained in Confederate hands is unclear, although the military records all indicate that he was indeed a prisoner of war at some point. After his capture at Ream’s Station, he may have been sent to Libby Prison in the Confederate capital, Richmond. Another soldier taken that day, George E. Albee, 3rd Wisconsin Light Artillery and Company F, 36th Wisconsin Infantry, was sent there, as noted in his 1864 diary. He was eventually exchanged and lived to rejoin his family. Another captured soldier from Ream’s Station was Edward Anthony of the 3rd New York Cavalry; Anthony was also held at Libby then Andersonville Prison, and died of an unknown illness in Macon, Georgia, that September. Others captured that day ended up at Salisbury Prison in North Carolina.

The final muster roll notation was that handsome Johnny died 4 April, 1865, “of disease,” with a note appended beneath, “in Rebel prison.” However, a pension application submitted on his mother’s behalf noted that “John Quick died 4 April, 1865, at Harrisburg, Pa. (Camp Curtin) of typhoid fever and scorbutus [scurvy].”

A Federal training camp named after the Pennsylvania governor Andrew Gregg Curtin, “Over 300,000 soldiers passed through Camp Curtin, making it the largest Federal camp during the Civil War. Harrisburg’s location on major railroad lines running east and west, and north and south made it the ideal location for moving men and supplies to the armies in the field. In addition to Pennsylvania regiments, troops from Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Wisconsin, and the Regular Army used Camp Curtin. The camp and surrounding area also saw service as a supply depot, hospital and prisoner-of-war camp. At the end of the war, Camp Curtin was used as a mustering-out point for thousands of troops on their way home. It was officially closed on November 11, 1865,” states the Camp Curtin Historical Society.

Camp Curtin’s hospital was John Quick’s last stop on a long road through a terrible war. Weakened by a facial wound and a sojourn as a prisoner of war that resulted in scurvy, this brave man who had survived the carnage of countless battles and skirmishes finally succumbed, so very close to home. His death was not by a bullet or bayonet, but by a disease born of contaminated water or food. Typhoid is excruciating, with high fever and diarrhea that leads to dehydration, delirium, intestinal hemorrhage, septicemia, or diffuse peritonitis. We can only hope that John passed quickly. He was most likely rapidly buried at Camp Curtain in a grave unmarked today.

As for his mother Ellen Quick, the pension application states that “credible witnesses testify that all the property of claimant consists of the income of seven pe’ct interest on $1200. Support by son shown before and after enlistment.” John, it seems, had sent his pay home to his mother. On 13 January, 1866, Ellen was granted a pension of $8 per month, backdated to April 1865.

Four years later, Ellen was listed the 1870 census of Covert, dwelling with her son-in-law, 49-year-old retired farmer Cornelius Peterson, and her daughter Harriet. Ellen, who was then 71, was listed as having no occupation but she had real estate valued at $1,400. She died 8 August, 1878, at age 79. Harriet lived more than three decades afterward, dying 14 December, 1914.

After his tragic death, the 1850s daguerreotype—most likely the only image of John Van Der Ipe Quick in existence—was taken to a studio so that CDV copies could be made for his mother or other relatives. Never a husband and father, the image is John’s only legacy. Ω

I have decided to occasionally reblog the excellent content of other history blogs. This site, Unremembered: A History of the Famously Interesting and Mostly Forgotten, is made of the same stuff as Your Dying Charlotte; to wit: “Let these people and these stories not be forgotten.”

By Ken Zurski

Beginning in 1712 and continuing for nearly 150 years, the British monarchy used soap to raise revenue, specifically by taxing the luxury item. See, at the time, using soap to clean up was considered a vain gesture and available only to the very wealthy. The tax, of course, was on the production of soap and not the participation. But because of the high levy’s imposed, most of the soap makers left the country hoping to find more acceptance and less taxes in the new American colonies.

Cleanliness was not the issue, although it never really was. Soap itself had been around for ages and used for a variety of reasons not necessarily associated with good hygiene. The Gauls, for example, dating back to the 5th Century B.C., made a variation of soap from goat’s tallow and beech ashes. They used it to shiny up their hair, like…

View original post 689 more words

The second of an occasional series.

Ω

“Yet in these ears, till hearing dies,

One set slow bell will seem to toll

The passing of the sweetest soul

That ever look’d with human eyes.”—Alfred Lord Tennyson

This poignant American brooch, which measures about 1.75 inches tall and dates to the late 1860s, contains a tintype image of a boy of about eight years wearing a wool jacket. Around the inner rim of the viewing compartment is a thin braid of blond hair, presumably that of the child in the photograph.

The brooch has a unique swivel mechanism that I have never seen before. Usually, the brooch body revolves to bring to the front a second viewing compartment (in this case the back side contains only checkered silk). On this brooch, however, it is the pin mechanism that rolls to whichever side will serve as the reverse.

This lovely American woman, who is pictured in fashions of about 1850, once looked out at those who loved her from the black enamel setting of this mourning brooch just as she now studies us, the denizens of an age perhaps unimaginable to her. The daguerreotype is delicately tinted to give her cheeks the rosiness of life and to highlight her gold brooch and earrings.

This large rolled gold brooch contains a ruby ambrotype (an ambrotype made on red glass) of a beautiful English woman whose first name, Emily, is inscribed on the reverse. It dates to about the same year as Beverly Wilgus’s brooch, above. Ω

This mid-1850s, whole-plate daguerreotype of a woman and three children is from the collection of Beverly Wilgus, another of the antique photo collectors of Flickr who has graciously allowed me to present her images. Of it, she writes, “[W]e have had the glass replaced by a conservator. It is our only whole plate daguerreotype (6 ½” X 8 ½”), which is the largest size that was in common production…. I have been asked why there is not father with the family. While it is possible that the father is deceased, I like to think that the photograph was a gift for him.”

If this image was a gift for Father, it was almost certainly purposefully posed to remind him, or any viewer, of his absence—the blank space in the middle the group screams to be filled. It is reminiscent of the portrait of the Bronte sisters, now known as the “Pillar Portrait,” which hangs in the National Gallery in London.

Painted in 1834 by the sisters’ talented, ego-driven, and alcohol-fueled brother who was then attempting to become a portrait artist, Branwell Bronte chose to eliminate himself and insert a column instead. It has been argued that he felt the composition was too crowded or that it was done in high dudgeon—we may never know which for sure. Charlotte died in 1855, at about the same time as Beverly’s daguerreotype was taken. After the death of Charlotte’s father in 1861, her husband, the Reverend Arthur Bell Nicholls, cut the painting from its frame, folded it up, and took it with him to his native Ireland, where it languished for many years. During that time, the “ghost” of Branwell began to appear through the paint—part spectral bogeyman, part prodigal son.

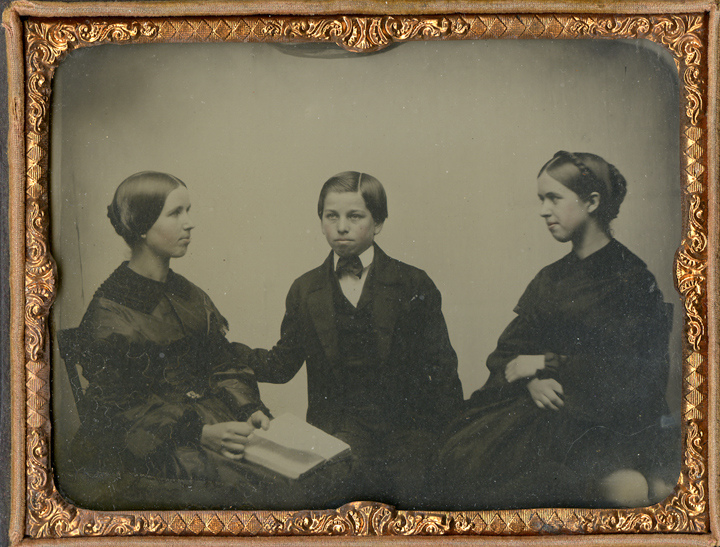

Another of Beverly’s images—this one an ambrotype also taken in the mid-1850s—again makes use of empty space to convey the message of loss. And in this image, it is indisputably death that has struck twice, leaving two pointed shapes like stab wounds between the three young people. A “reader” of this portrait, and it was yet very much a time of encoded meanings in art and photography, would know immediately that the teenage girls wore mourning gowns: the dark, wide lace collars of their dresses leave no doubt that the entirety of their costume is black. Between them is their younger brother, now the man of the family, reassuringly touching his elder sister’s arm. He seems stoic but unprepared for the task.

This final image used props to fill the void caused by death. Whilst the husband and wife focused on a point stage left (she almost certainly dressed in mourning), between them sat a plant stand covered by what must have been a colorful, almost childish string doily, upon which an elaborate picture frame was placed. It contains an image a girl and possibly a boy. The message can be taken no other way: “These were our children; now they are no more.” Ω