The subject of this CDV is Eliza Schuyler Kuypers, wife of Ethan Alphonso Allen (8 February, 1818-27 November, 1889). Eliza’s husband was the grandson of the American patriot, farmer, philosopher, deist, and writer Ethan Allen (1737-1789) and his second wife Frances Montressor (1770-1834), through their son Ethan Voltaire Allen (1789-1845) and wife Mary Susanna Johnson (26 Sept., 1797-1 November, 1818).

Eliza, born in 1820, was the great-granddaughter of Elizabeth Schuyler (1771-1801) and her husband Rev. Gerardus Arentz Kuypers of Curacao, Dutch West Indies, who had been born on the island in December 1766 and later came to Hackensack, New Jersey, then to Rhinebeck, New York, to minister to the Dutch community there. Eliza’s grandfather was their son, also named Gerardus Arentz Kuypers (1787-1833), who was educated at Hackensack, and then studied theology under his father. He was licensed to preach in 1787 and served as a collegiate pastor in Paramus, New Jersey. In 1780, he moved to New York City to preach in the Dutch language. In 1791, he earned a Master of Arts degree from the College of New Jersey, as well as a Doctor of Divinity from Rutgers in 1810. It is noted that he suffered from asthma but died of “ossification” of the heart 28 June, 1833.

Eliza was the daughter of his son, Dr. Samuel S. Kuypers (8 March, 1795-10 January, 1870) and Amelia Ann VanZant (1794-1864). Dr. Kuypers was an alumnus of Rutgers and a member of the Medical Society of the County of New York from 1820 until his death.

In the CDV image above, Eliza is most probably wearing mourning after her mother’s death in the penultimate year of the Civil War. Amelia VanZant Kuyper’s demise was announced in the New York Times of 8 January, 1864, as follows: “On Thursday, Jan. 7…in the 70th year of her age. The relatives and friends of the family are respectfully invited to attend the funeral from her late residence, No. 142 2d-av., on Sunday, Jan. 10, at 3 o’clock p.m. without further invitation.”

Continue reading “The Patriot’s In-Law: Eliza Schuyler Kuypers”

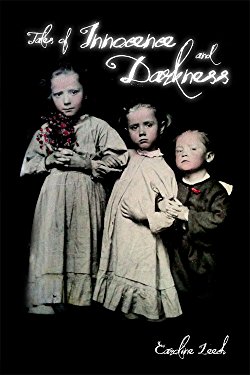

“I then developed an interest in spirits and faeries and fell in love with writers such as my beloved Charles Dickens, Sheridan LeFanu, Emily Dickinson and with the whole world of Victorian spiritualism, mourning, the faery painters of the time and also the darker aspects of Victorian society.”

“I then developed an interest in spirits and faeries and fell in love with writers such as my beloved Charles Dickens, Sheridan LeFanu, Emily Dickinson and with the whole world of Victorian spiritualism, mourning, the faery painters of the time and also the darker aspects of Victorian society.” “I live in a watermill in the middle of a forest, which is always an inspiration to me. I feel I am surrounded by all sorts of spirits.”

“I live in a watermill in the middle of a forest, which is always an inspiration to me. I feel I am surrounded by all sorts of spirits.” “I have been an antique dealer and visionary artist for years and am also a keen amateur photographer of anything mysterious. My greatest love is of course Victorian photography, these amazing ghosts which pleasantly haunt the pages of my book and the drawers and cabinets of my bedroom.”

“I have been an antique dealer and visionary artist for years and am also a keen amateur photographer of anything mysterious. My greatest love is of course Victorian photography, these amazing ghosts which pleasantly haunt the pages of my book and the drawers and cabinets of my bedroom.” Caroline’s book of photos and poetry can be purchased at

Caroline’s book of photos and poetry can be purchased at