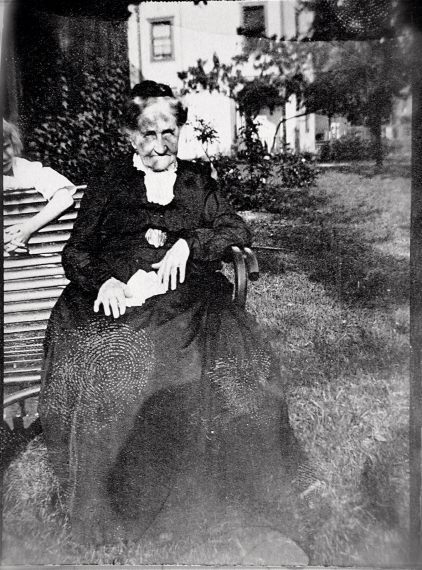

Lavada May Dermott, seen above laid out in her parents’ home, surrounded by funeral flowers, was born 9 May, 1888, in Goshen, Belmont County, Ohio, to Charles Evans Dermott (1849-1907) and his wife, Sarah Jane Stewart (1853-1936). Sarah was the daughter of Eleazar Evan Stewart (1834-1910) and Honor Brown (1835-1914).

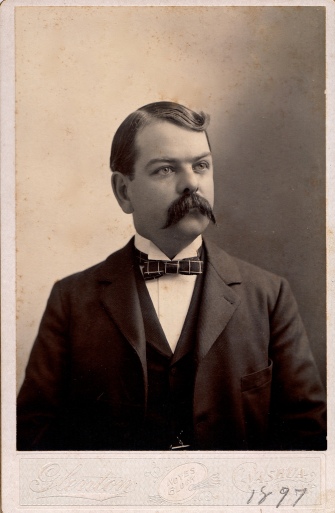

Lavada’s parents married in Goshen 26 January, 1871. They first make an appearance as a family unit on the 1880 Census of that township. Evans Dermott—he went by his middle name—listed his occupation as “huxter.” His father, Irish-born farmer William Dermott (1811-1896) was also a part of the household—his wife, Eliza Kelly (1813-1879), having died the year before.

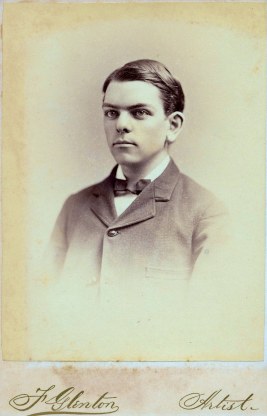

Evans and Sarah had together four children: William Wilber (1871-1947), Charles E. Dermott (19 June, 1881-23 September, 1944), Lavada, and Lillie F. Dermott (1895-1987). On 20 May, 1900, the eldest son, William, married Grace Stanley King. William spelled the family name as Der Mott and is buried thusly in Forest Rose Cemetery, Lancaster, Ohio. By 1910, the Der Motts lived in Cleveland, Ohio. William became a garment cutter for a clothing company and eventually was the manager of a clothing store. He worked in that position as late as 1940. They had two children: Neil (b. 1902) and William P. (b. 1903).