I have in my collection this incomplete letter from the mid- to late 1800s written by an American woman named Julie who had endured the loss of her fiancé, Freddie. Julie’s letter was for another woman—her elder and probably close family friend, Mrs. Crane.

Julie and Freddie were young, possibly in their teens. Julie was quite literate, but her writing contains numerous errors, phonetic spellings, and a general disuse of commas, full stops, and quotations that is endemic to the era. I have corrected her mistakes and added modern punctuation in the quotes below.

“I sat and looked at him all night,” Julie wrote at the top of the single page, recalling the aftermath of the passing. “So many spoke of his smiling and happy beautiful countenance even in death. He looked too beautiful to bury.” She then hopped backward in time, writing, “He was sensible until two minutes before he died, but whether he realized he was really dying, I know not.”

Next she confides in Mrs. Crane, “About two hours before he died, I sat crying and he looked at me. I said, ‘Freddie darling, how can I give you up?’ He raised his hand and said ‘Oh, Julie, don’t.’”

Don’t? Don’t weep? Don’t imply that he was dying? Don’t tarnish his “good death” with female hysteria? Perhaps Freddie’s command was more prosaic: The dying man needed to move his bowels. “[H]e wanted to get on the chamber [pot] and I asked him if I should tell his mother. He said, ‘Mother is weak.’ I said, ‘Freddie, shall I help you?’ He said, ‘Yes, please,’ so I [assisted] him,” she next wrote. Of all the letter’s painful details, this strikes deepest—a heartbreaking intimacy, demanded by circumstance, between a couple who may never have seen each other unclothed.

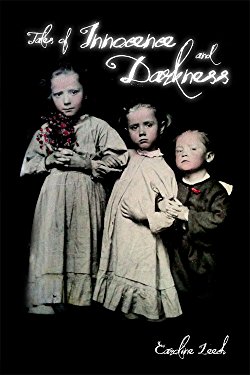

“I then developed an interest in spirits and faeries and fell in love with writers such as my beloved Charles Dickens, Sheridan LeFanu, Emily Dickinson and with the whole world of Victorian spiritualism, mourning, the faery painters of the time and also the darker aspects of Victorian society.”

“I then developed an interest in spirits and faeries and fell in love with writers such as my beloved Charles Dickens, Sheridan LeFanu, Emily Dickinson and with the whole world of Victorian spiritualism, mourning, the faery painters of the time and also the darker aspects of Victorian society.” “I live in a watermill in the middle of a forest, which is always an inspiration to me. I feel I am surrounded by all sorts of spirits.”

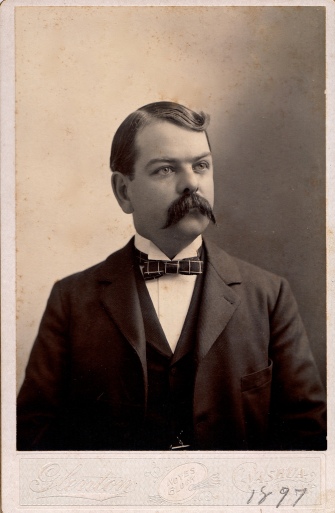

“I live in a watermill in the middle of a forest, which is always an inspiration to me. I feel I am surrounded by all sorts of spirits.” “I have been an antique dealer and visionary artist for years and am also a keen amateur photographer of anything mysterious. My greatest love is of course Victorian photography, these amazing ghosts which pleasantly haunt the pages of my book and the drawers and cabinets of my bedroom.”

“I have been an antique dealer and visionary artist for years and am also a keen amateur photographer of anything mysterious. My greatest love is of course Victorian photography, these amazing ghosts which pleasantly haunt the pages of my book and the drawers and cabinets of my bedroom.” Caroline’s book of photos and poetry can be purchased at

Caroline’s book of photos and poetry can be purchased at